The GP came around one lunchtime and hugged me. ‘Remember,’ he said, ‘you’re his daughter, not his doctor.’ I cried, briefly, and it helped.

Then he was back off on his rounds, and I was back to being the carer who was supposed to know what she was doing. But it helped. So lesson one is: be kind, and don’t be afraid to hug.

Dad was there when each of us was born, and we were all with him when he died

We’re a big family, and I don’t know how small families cope with a death at home. Even with daily visits from the lovely district nurses, and a nurse and a doctor in the family, and six of us helping each other, and extended family running around after us all, it was hard.

But it was the right place for him to be. My brother gave the eulogy at his funeral and he said: ‘Dad was there when each of us was born, and we were all with him when he died.’

And that was something to treasure. Lesson two: have a big family. Or at least, it takes a lot of people for a good death at home.

We’d known the leukaemia was progressing for a while, and one day Dad was so short of breath and in such pain that we took him to the emergency department. It was grim.

Lesson three: give open access to the ward. It would have saved him from the junior doctor who was so interested in his huge palpable spleen that he made the abdominal pain even worse.

Dad turned to me, ‘But what will happen if I don’t take my medication?’

Hours later we saw the consultant. A good man, trusted implicitly. He said: ‘I’m afraid we can’t do anything; go home, be with your family, stop all medication.’ He left.

Dad turned to me, ‘But what will happen if I don’t take my medication?’ Lesson four: don’t do that. Don’t be nihilistic, don’t destroy hope, even if it’s only the hope of a comfortable death.

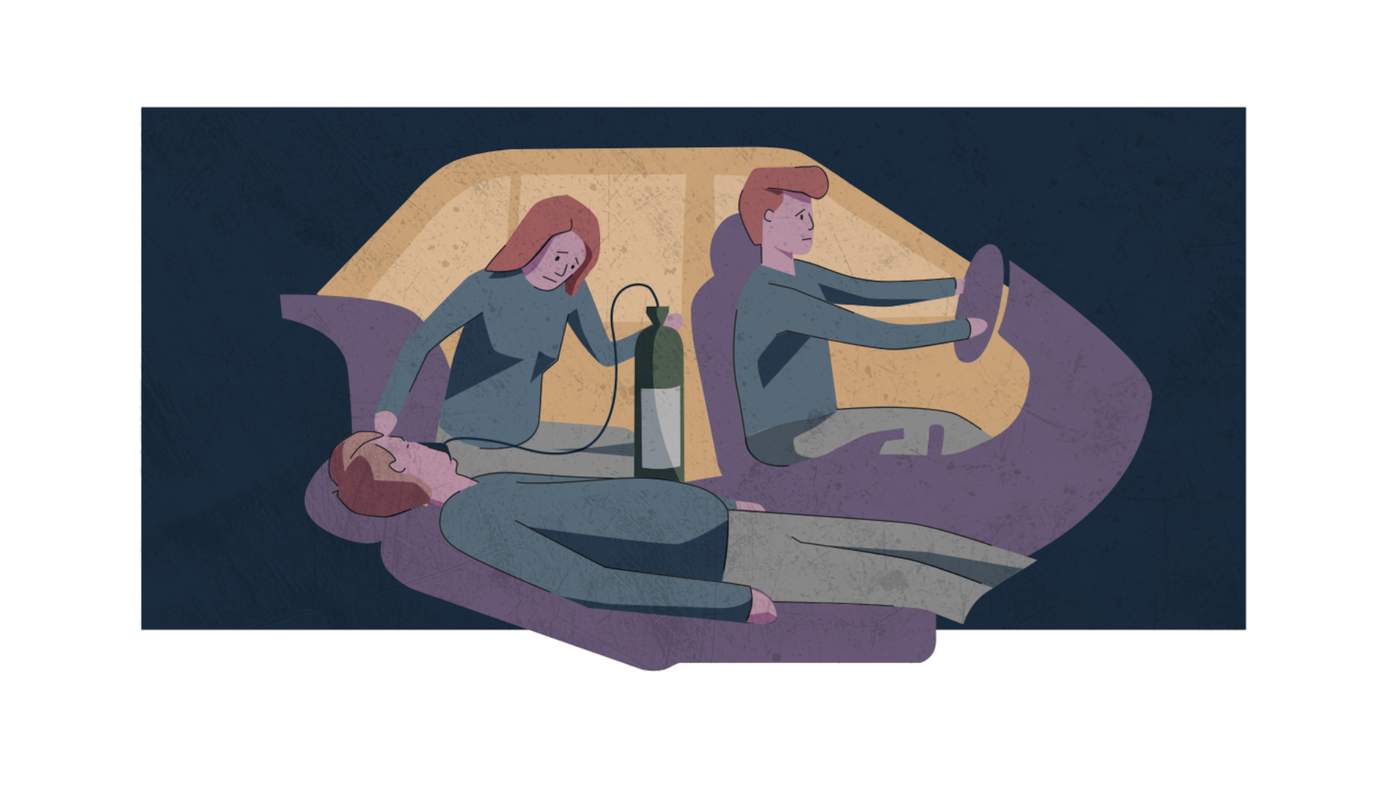

Then we couldn’t get an ambulance. We waited and waited, and the ward was full and we were sitting on hard chairs in a corridor. Dad was distressed and looked near death.

So we did an ‘AMA’, laid the front seat of the car as flat as it would go, my three strong brothers manhandling Dad in so gently.

We drove away with me crouched behind carefully cradling the oxygen cylinder, the oxygen cylinder that made this flit possible, the oxygen cylinder so kindly and miraculously produced by a tender-hearted nurse.

Lesson five: kindness trumps bureaucracy; do what needs doing. Time is short.

Dad rallied a bit at home, and we had precious days. But symptom control should have been better.

Confusion, pain, urinary retention, nausea; and we weren’t always sure what to do, or who to ask. I wish we could have had a palliative care consultant. Lesson six: be proactive, get expert advice. Ask. Visit.

We all sat with him and took it in turns to read aloud, and then he was calm

He tried to wander round, looking for something he said he was waiting for. He had more strength when he was confused, so we let him walk, one of us on either side, till he settled in the sitting room.

And we all sat with him and took it in turns to read aloud, and then he was calm.

We read Three Men in a Boat, and we laughed. We talked. I said to Dad: ‘Did you really mean to have five children?’ and from out of his fog, Dad said: ‘No, we wanted six.’

And later, when I wasn’t even sure he could hear me, I said: ‘I love you so much. You’ve been a wonderful father.’ And he smiled, and said: ‘I still am.’ Lesson seven: I don’t really know, I just know there’s a lesson in this bit too.

An agency nurse came round to spend the night. She looked at me and said: ‘You’re the doctor daughter? I don’t like doctors.’

She went upstairs and rearranged the furniture, sat by his bed and said: ‘Now everyone just chat, have a good gossip; they love to hear chit-chat.’ They? She wouldn’t give him his rescue dose of morphine when he groaned in pain because of Harold Shipman. My sister got rid of her. Lesson eight: don’t be a tit.

I remember all of us round his bed, with the sun streaming in, Dad exactly where he wanted to be, Mum by his side

The out-of-hours GP came in the night and sorted his morphine; we propped him up in bed, sitting either side, and in the morning he died with his head on my shoulder.

This was more than a decade ago; but I remember every moment.

I remember so much kindness, and so much love, and laughing, all of us round his bed with the sun streaming in, Dad exactly where he wanted to be, Mum by his side.

So this story is about a good death, and the lessons I learned.

And all the lessons are the same lesson: be kind.

The winner of this year's BMA writing competition is Warwickshire GP Felicitas Woodhouse (pseudonym).

Credits

Author: Felicitas Woodhouse (pseudonym)

Content editor: Neil Hallows

Digital producer: Sarah Quinlan

Production editor: Chris Patterson

Senior designer: Tim Grant

Senior digital producer: Karen Lobban

Senior production editor: Kelly Spring

Title illustration: Daniel Burgess