Born of injustice

As we reported in Separated at birth, junior doctor Carrie Adams had her baby taken away when she was a day old.

Now, with the BMA's help, she has won the right to reveal what happened to her. Psychiatrists say mothers with unmet mental health needs are being unnecessarily parted from their children.

*Names have been changed

Carrie Adams,* a junior doctor and mother of two, is back in family court. The same one which ordered her first child, Evie,* to be removed, a day after she was born. She’s to face the same judge, who agreed after nine months for her daughter to go home.

But Dr Adams is here today, years later, under very different circumstances.

She’s helping The Doctor and BMA lawyers to obtain private papers which might reveal shortcomings in her care to help others with mental ill health by letting them in on intimate details of her experience. But right now we’re waiting, sharing her biscuits and family snaps (there’s Evie on a bridge in the park, beaming, mum behind her). We’re sitting on metal chairs, encircled by locked courtrooms, keeping company with anxious parents, their weak smiles seemingly seeking solidarity.

We’re bringing this action amid growing concern about childcare cases. Doctors are struggling to convince courts that mothers with mental ill health can and should be treated instead of separating them from their babies.

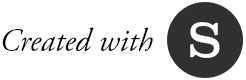

One recent study, Born into Care by the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, found a doubling in the number of newborns caught up in family courts between 2007-08 and 2016-17.

‘In my view, there are gross miscarriages of human rights going on,’ says South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust consultant perinatal psychiatrist Trudi Seneviratne, who chairs the RCPsych’s (Royal College of Psychiatrists) perinatal faculty.

‘We’ve got this expansion of [MBUs] mother and baby units in England, which is great. But our local authorities and legal processes don’t understand that these mothers’ conditions are treatable.’

A wall of doubt

Source: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory

So what’s going on? What can the case of Dr Adams tell us?

Our time with the judge is over in minutes. Reports are released and in our hands. They reveal much, tragically, about the way Dr Adams and other mothers with mental ill health are treated by councils, the courts, and the NHS. The struggle to get help. Desperation as the due date approaches. The accusations. The wall of doubt that your illness is treatable, that you’ll be well enough before the case concludes. There’s also the stigma, which Dr Adams faced, unbeknownst, as a patient and doctor.

Her first contact with professionals in the case was at a booking appointment 10 weeks into pregnancy by IVF. There and then she disclosed her mental health problems: depression, anxiety and OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), according to reports by her senior specialist midwife. She’d stopped medication ‘due to her pregnancy’ (other court papers point to her worries about how medication ‘would impact on the baby’). She claims support from family and friends at that meeting. She is referred to a vulnerable babies’ service and perinatal psychiatrist. But her appointment with the specialist doesn’t come through for four months.

There’s more contact with midwives at weeks 14 and 21, when she speaks of worsening OCD symptoms. Her care transfers to a female obstetrician as she ‘refused to be seen by a male doctor’, the midwife reports. She ‘would not allow’ an intimate examination, making ‘safe management of labour difficult’ (a fear of contamination and men, at the time, is linked to the OCD in other court papers). She elects to have a caesarean section on safety grounds.

At 24 weeks it’s noted, ‘she had no support at home’ but then toured a ward with her mum and ‘formed a plan with the supervisor of midwives’. Dr Adams is described by the senior specialist midwife as ‘extremely articulate’, a doctor with the ability ‘to gloss over her difficulties’ with professionals. There’s concern about her ‘lack of attachment’ as she’d referred to her unborn baby as ‘the child’. ‘My main concern is for the emotional well-being of the baby,’ the report says.

Questions about the midwives’ relationship with Dr Adams are raised by a court-appointed consultant psychiatrist, three months after Evie was removed.

Calling an unborn baby ‘the child’ was ‘quite normal’. She had called hers ‘Wrigglesworth when active’ too, it says. ‘She had started to have a relationship with affection and some humour before delivery.’ Her behaviour was ‘fitted to an assumption that she will be incapable of normal bonding’, it adds. ‘There was considerable scepticism and tension in the relationship with Dr Adams and the midwives.’

Four months before her due date, Dr Adams becomes desperate for treatment, calling her specialist midwife in a ‘stressed state’. She is ‘despondent about getting her mental ill health sorted in time’. She expressed suicidal thoughts, the court papers add. Weeks later she’s assessed by an experienced clinical psychologist, who then sees her regularly.

Concerns mount

Dr Adams admits she ‘laid it on with a trowel’. ‘My fear wasn’t that they would take the baby away, but that the help wouldn’t be there,’ she says.

Court papers show there were episodes of depression, an overdose in her teens, and some self-harm. The court-appointed psychiatrist ‘tried to makes sense’ of her struggle to get treatment. ‘NHS protocols’ were likely to blame, they say.

She was eventually seen by a perinatal psychiatrist some six months in. But after a ‘detailed assessment’ at that appointment it is ‘clearly envisaged’ her baby would go home, the papers say.

A few notable incidents are recorded in the following weeks. She misses a single appointment with an anaesthetist (a sign of ‘poor engagement’, they say; she attended ‘the majority of her antenatal appointments’ the senior specialist midwife notes). A blood test finds anaemia. ‘I took iron tablets,’ Dr Adams says. A social worker notes a ‘bad day’, after ‘brushing her bag against a man on a bus’. A week later, children’s services decide not to get involved, following a ‘vulnerable babies’ meeting.

With her due date approaching, she is seen by a community psychiatrist who finds she is ‘looking forward to the birth’ but admits there’s rubbish ‘everywhere in the house’. She’s struggling to clear it up. There’s mice. Her mum helps but there’s no ‘concrete plans’ to sort things out, the community psychiatrist says. She is ‘engaging’ with treatment and staff, still not willing to consider medication, but ‘is hopeful the psychotherapy will help’, their record adds.

Two weeks later a ‘meeting of professionals’ is called amid ‘increasing concerns’ about her mental state. She’s not invited. There’s a ‘unanimous decision’ to refer to children’s services. Days later, a date for a caesarean section is set.

A letter from her psychotherapist to that professionals meeting – which they could not attend – describes her as ‘committed’ and ‘motivated’, that she’d made an ‘important step forward’ in her therapy. They advise extra support in the ‘early days following birth’ and that her mother is moving in. It points to the support of two friends (a GP and paediatrician, The Doctor has confirmed).

Dr Adams sought legal advice after social workers told her of their concerns but thought the plan she had agreed with midwives was in place: some days with support on the ward that she had toured with her mum. But the day before admission, a woman she considered a close friend called the senior specialist midwife anonymously ‘expressing serious safeguarding concerns’. The same woman later submitted a 57-page letter to the court. The ‘majority of points’ it raises had already been disclosed by Dr Adams, court papers confirm.

On the day of the operation, the professionals meet again. They decide to seek an emergency protection order to remove Evie several days after her birth. The perinatal psychiatrist refuses a bed on an MBU, saying the ‘chronicity’ and severity of her illness makes it ‘highly unlikely’ she would improve in a ‘few weeks’. ‘Dr Adams was not aware of the decision at the time,’ a note of that meeting says.

Meanwhile, she walks into theatre to deliver.

‘Evie came out howling her head off, arms and legs going,’ she says of the birth. ‘I was told I had a daughter. I got to see this cute button nose, a perfect little ear. Mostly, I’m in a state of shock. She’s here. The world has changed. My world has changed. It was overwhelming.’

3am the next morning, she’s up, attempting to breastfeed, helped by midwives and her mum. 9.10am, her obstetrician notes, ‘she appears comfortable and confident with baby’. 11.05am, she shows signs of distress. Her mum says the crying ‘is too loud for her’. 12 noon, she vomits. At 2.45pm, she’s found in a corridor, distressed, asking for help.

Minutes later, she reports feeling unwell, asks for blood tests (she’s not eaten since the operation). Half an hour later, a hook on the wall is ‘turning into a spider’, she says. The psychiatric registrar is called. They urge sectioning under the Mental Health Act if she tries to leave.

Hours later, social workers accelerate the removal, asking the police to attend. Then the notes fall silent. Until after Evie’s removed. Dr Adams recalls being confronted by a police officer in a tactical vest, a social worker, midwife and psychiatrist, as she sat on her hospital bed. ‘I just started to cry because I knew why they were there. There was no other reason.

’They tried to detain her under a Mental Health Act section but didn’t. She stays overnight. The next morning her community psychiatric nurse arrives, speaks of a ‘knee-jerk reaction’. Then she’s discharged. Her discharge note, according to court papers, records a ‘low blood haemoglobin’ of 82 grams per litre, ‘significantly below normal (130-150)’.

Days later, Dr Adams faces the judge for the first time and an interim care order is granted. The council claims her condition makes it ‘impossible for her to be able to care adequately for a young baby’. It cites evidence, of hour-long showers and that Dr Adams disputes this; of her distress ‘if something drops on to the floor’. Her baby crib was ‘covered with cellophane’ to prevent ‘contamination’.

Contradictory findings

The court-appointed psychiatrist, however, finds the ‘decision-making’ leading to Evie’s removal to be ‘not entirely clear’ in their report, three months on.

‘She had responded positively to the baby, shown signs of early bonding and engaged in breast feeding,’ it says.

‘The difficulties she had were primarily related to physical problems, not her OCD.’ Police records show she was seen as ‘difficult’ and ‘compared unfavourably with other mothers by NHS staff’.

‘The factual basis for this is not clear,’ the psychiatrist adds. ‘Most of the observations were within 12 to 18 hours of a caesarean section. She describes clear evidence of mild confusion and has been vomiting and bleeding.’

A week later, social workers find Dr Adams is ‘clearing the house’. Days later, her perinatal psychiatrist describes her as ‘considerably improved in her functioning’ but refuses her appeal for a bed on their MBU. She’s discharged from perinatal care to the community team and her community psychiatrist also asks for an MBU bed. ‘She was not accepted,’ their record says.

The court-appointed psychiatrist, who is not a perinatal specialist, equivocates about reuniting Evie with her mum in an MBU in their report. It ‘would not be optimal’, ‘probably not the best approach’ but ‘one that could potentially be considered’. It flags concerns about ‘increased symptoms in a shared environment’.

The RCPsych’s Dr Seneviratne is, however, clear that Dr Adams should ‘absolutely’ have been given the chance to stay with Evie in a psychiatric MBU. ‘She had a history of chronic anxiety, depression and severe OCD. These aren’t reasons to remove a wanted baby even if there was something else underlying those conditions,’ she says. ‘We know that medication can work in anxiety disorders but we also absolutely know that some people respond really well to psychological therapy.’

Over the nine months of their separation, Dr Adams sees Evie a few hours a week, supervised by contact workers. She continued therapy.

Three months after Evie’s removal, ‘important inroads’ have been made into changing her ‘long-standing pattern of severe difficulties’. Her therapist notes ‘important behavioural change’. By month four, she is no longer troubled by the concept of ‘dirtiness’. Month five, she’s picking up dropped objects without washing her hands.

Despite improvements early on, the court-appointed psychiatrist questions whether sufficient progress can be made to meet Evie’s emotional and development needs. But no such concerns are raised by the ISW (independent social worker) in a later assessment, six months after removal.

The contact centre workers, who supervised her time with Evie, describe it as ‘superb text book’, the ISW report says. ‘I hold no concern about the ability of Dr Adams or her mother to meet the basic needs of Evie and to provide high levels of emotional warmth,’ it adds. Her mum, who moved in shortly after Evie’s removal, is called a ‘stabilising factor’ and ‘eminently suitable’ to act as a safeguard if her mental ill health relapses.

A month on, another report from the court-appointed psychiatrist finds Dr Adams ‘symptom free’ and a ‘good chance that she will be able to parent reasonably well’.

The next month, her psychologist describes her prognosis as ‘good’. The next, Evie is back home.

So what lessons can be learned from this case?

That mothers should never be separated from children, especially their firstborns, unless absolutely necessary? That NHS units for mothers and babies are there to be used? That the stigma around mental ill health is alive and well in the health service?

Perhaps it’s that the traumas of separation will always be carried, will always remain with the mothers who bear them. When leaving the court, Dr Adams insists on a visit to its mother and baby room. ‘I didn’t know it was there,’ she says. ‘The whole time I was here.’

Perhaps the lesson is just that mental ill health is treatable without such trauma. It’s something of which many still need convincing, be they councils, the courts or the NHS.

We must learn from Carrie's case

Gary Wannan is deputy chair of the BMA consultants committee and a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist

Our investigation into the removal of Carrie Adams’s daughter raises serious questions about her treatment.

We’ve found tensions in her relationship with her midwives. That she struggled to receive consistent help for her mental ill health before giving birth. On the ward, the confusion of this known-anaemic new mother, post-op, was assumed to be owing to her mental health. It’s appalling that a physical cause doesn’t appear to have been considered.

And why deny her and her baby a bed in an MBU (mother and baby unit)? While hindsight’s a great thing, it looks as though Dr Adams’s symptoms were eminently treatable. We don’t know all the details. But there’s enough evidence to suggest something went wrong, leaving Dr Adams with a trauma she’ll forever bear.

As in any area of medicine, we must soberly reflect on the evidence to learn lessons.

Mothers need to feel safe to disclose mental ill health and get help. How do we get there?

They need access to treatment, such as talking therapies, well before birth. Many are not, as the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory for England and Wales has found. Family court cases costs thousands.

Why not spend that on treatment instead, avoiding proceedings in the first place? It’s a point Bristol family court judge Stephen Wildblood QC repeatedly makes.

When risks to a baby seem high – or difficult to predict – families can often be kept together in MBUs until informed decisions are made. Not separated. More resources will help, as the Maternal Mental Health Alliance points out.

We need to reduce big swings from the extremes of a ‘hands-off’ to the reactive ‘full-on’ approach in how cases are managed. Professionals must work together in a clear and sustained way.

Then there’s the stigma about mental ill health in the NHS to be erased.

There’s much to be done and perinatal care will be a focus of BMA work this year. Sometimes it takes just one story to move us to further action. Let’s not forget this one.

Journalist Keith Cooper

Subeditor Chris Patterson

Design and animation Tim Grant