Hero doctors

The BMA Book of Valour –

remembering acts of heroism by doctors

‘You almost slip into a different mode, you’re focused on what you need to do clinically and are not exactly dehumanised, but trying to depersonalise it, so that you can do what you need to do.’

Dr Susan Butler

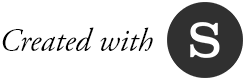

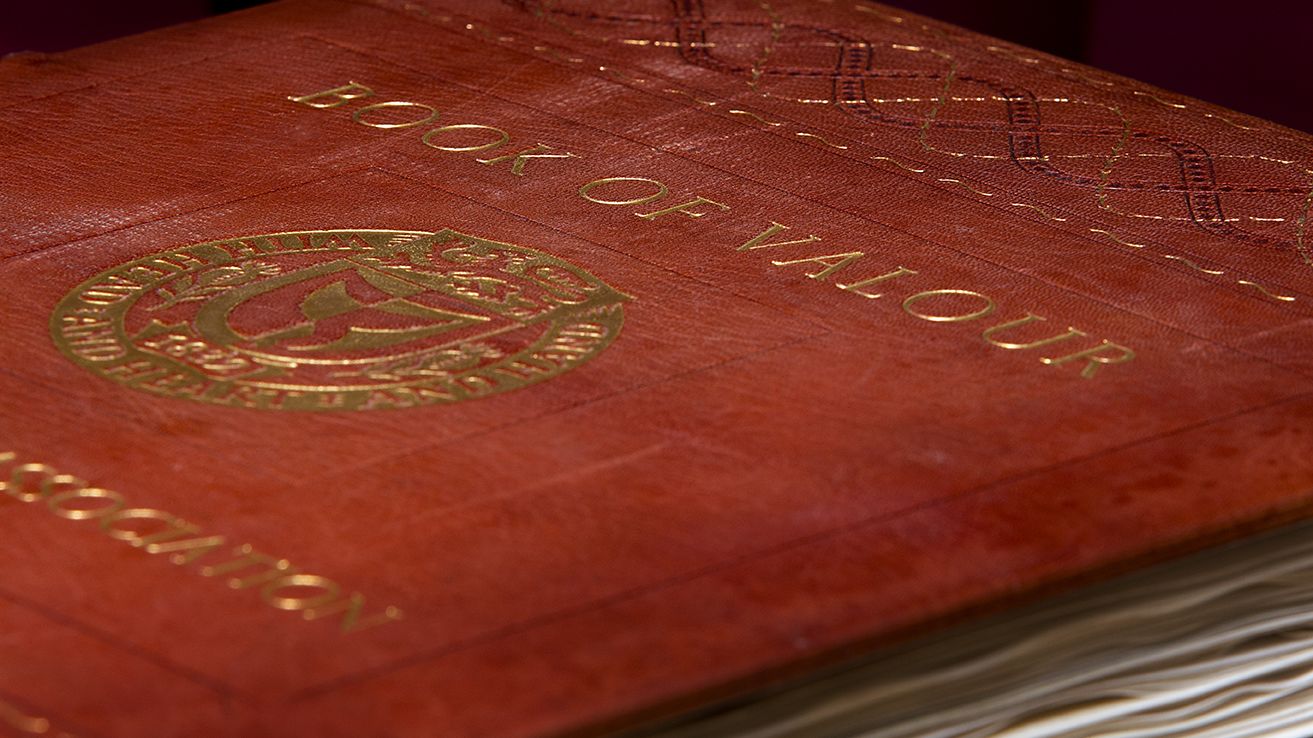

In 1956, eight years after the founding of the NHS, the BMA (British Medical Association) thought it was long overdue to find an appropriate way to recognise and celebrate acts of heroism by doctors.

At a meeting of the BMA’s representative body in Brighton, it was decided that a Book of Valour be created to record heroic deeds performed by medical practitioners.

The book would be a living document, forever on display at BMA House, and be a testament to the courage and selflessness of a profession.

Throughout the NHS, each day of their professional lives, doctors and medical practitioners demonstrate bravery and exceptional devotion to their patients.

We highlight a couple of exceptional examples from the BMA’s Book of Valour that have occurred during the lifetime of the NHS…

Trapped underground

Dr Susan Butler had passed the roadwork signs on numerous occasions. They were along Lister Street, not far from where she then lived with her husband in Ilkley, Yorkshire.

Local residents might have noticed slight delays to the flow of traffic in town but wouldn’t have given much thought to the cause; a new sewage system being constructed deep underground.

Dr Butler would get unexpected first-hand experience of the newly dug tunnel when a routine day at work as a senior house officer at Airedale General Hospital (West Yorkshire) was transformed into something much more eventful.

She would find herself administering medical aid to a trapped man, 25 feet below the surface, beneath tonnes of earth, in a tunnel at risk of collapse.

In March 1978, Dr Butler had been qualified for two years. A country girl at heart, she was enjoying her vocational training scheme in a more rural setting, having originally studied in Leeds.

Speaking to us 40 years after the dramatic events of that day, the details soon came flooding back as she takes up the story…

I was in A&E and going about my normal business.

I was just dealing with patients in cubicles with relatively minor injuries when the receptionist came in and said they wanted us to attend an incident in Ilkley where a tunnel had collapsed.

The chap, John Friel, was trapped and they didn’t think it was going to be a quick job getting him out so myself and one of the nurses from the hospital went down.

We ran a long-wheelbase Land Rover, which we took out to places where immediate medical help was needed. I had a Mini at the time so it was a big change for me to drive it.

The thing that I found difficult was the emergency signals that it gave off. I think all of us react to them and you don’t lose that when you’ve got medical training, so it used to make me feel hyped up when I was trying to calm down and think about what I would need to do when I got there.

‘I’m not that good with heights’

My most vivid memory is of looking into the hole and realising how big it was and particularly how deep it was, because I’m not that good with heights.

A fireman spoke to me and said a man was trapped and could I go down to take a look to assess him.

I was wearing my white coat and reasonably respectable clothes, which I seem to remember was a velvety skirt and a green jumper, and obviously I couldn’t go down like that, so he found me an overall.

He [the fireman] was very kind about my concern with heights and went down the ladder ahead of me. He took me down to the bottom of the ladder where the foreman from the tunnelling project met me.

The tunnel was off this huge hole – it wasn’t small, but it wasn’t big enough to stand up in. I think it was probably about four feet and shored up with a wooden frame.

Fifty yards in, there was no more tunnel, there was just earth with this chap sticking out of it. He was talking a lot, which in a way surprised me because he was completely buried below chest height. Knowing how deep down we were I couldn’t imagine that he wouldn’t be seriously injured.

I did wonder if, when he was released, any injuries would almost immediately affect him more seriously.

‘He was swearing a lot and the other guys were trying to be polite’

It was cramped and tense because the guy was very voluble and he was obviously very concerned about himself, but he was also very concerned for them as well. I think he knew that this was an unstable part of the tunnel and he kept trying to get them to go back and keep safe.

It seemed extraordinary, but at the same time I just tried to work through the normal kind of thinking that I might have used if he’d come into the emergency room.

I put up a drip assuming that there was going to be quite a lot of damage when he was finally extricated and that he might go into shock at any time and gave him some analgesics.

The place where they were digging ballooned out a bit from the tunnel so to get out of their way I edged into this wide part. I subsequently discovered that this contributed to their anxiety because this bit of the tunnel was actually the most unstable and they were afraid that a further collapse would occur and I would be in it.

They began to see some progress and suggested that I leave them to it so that they would have more space to extricate him so I went up and hung around at the top.

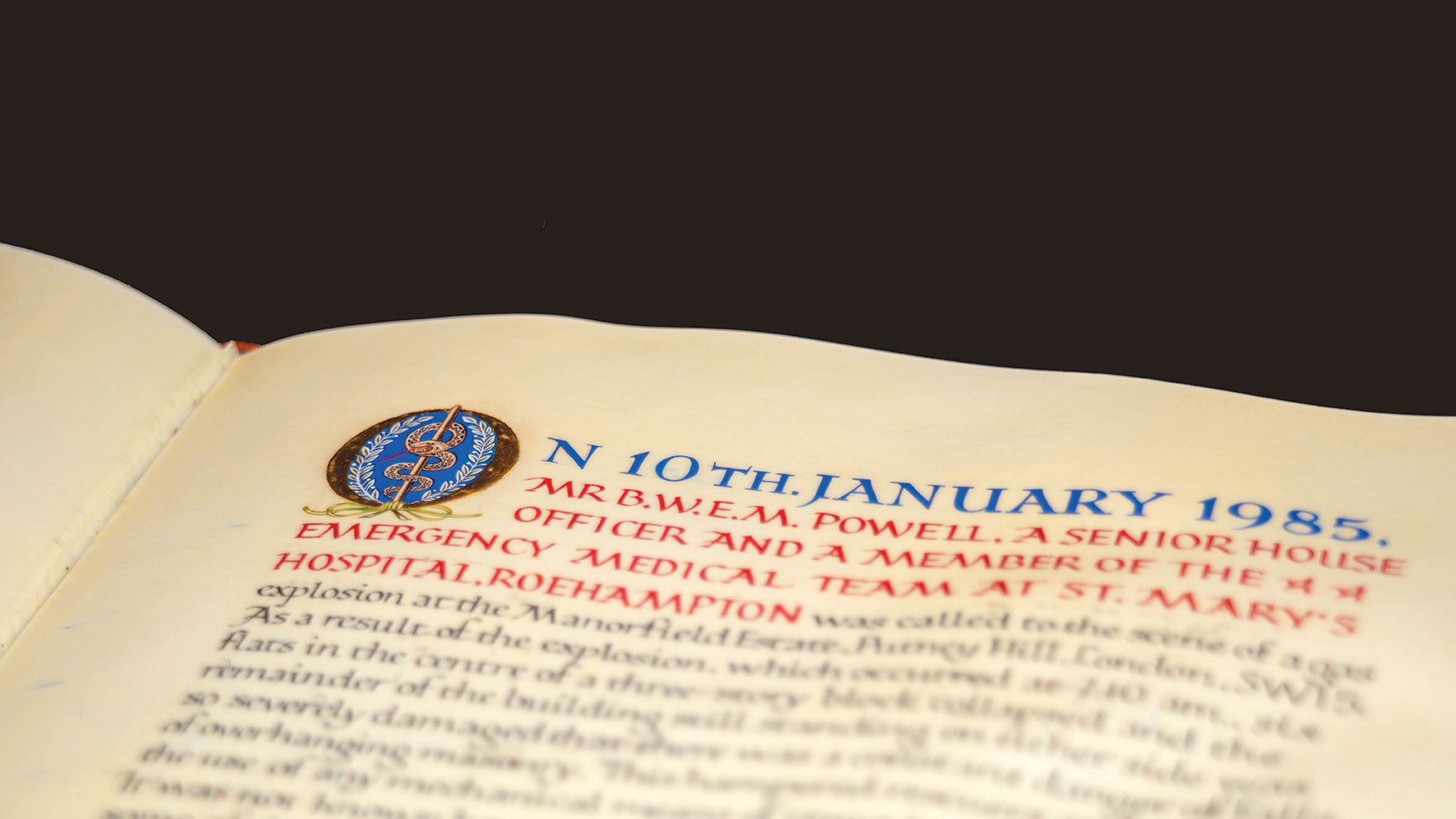

They hoisted him up out of the hole on some kind of pallet and to my surprise he was as he’d been in the tunnel; chatty, fully conscious, very voluble. We put him in the ambulance and I went back to the hospital with him.

He hadn’t been there long when his wife arrived with their three small children. I’m sure the prospect of being seriously injured or killed if the tunnel collapsed further was very terrible, not just for him, but for this young family.

He was a big chap and I presume that’s what saved him. He was built like a you-know-what. He wasn’t tall, but he was built like a bull. I think he returned to work the following week.

I think he was extremely fortunate and I really was surprised.

‘Don't think ahead of the game’

One of the things I learnt, which in a way I already knew but it reinforced for me – you don’t think ahead of the game. You don’t know what’s going on until you’ve assessed carefully what’s going on.

Back at the hospital, it was as if I hadn’t gone and nobody had been covering my work except the immediate emergencies while I was out.

Everything went straight back to being ordinary almost immediately, which I think in some ways minimised the effect on me because there was no time to think about what I had been doing. It was just back to ‘please show me where your cut is’.

They sent me some flowers which was very nice of them. The following week I answered the door and they asked me if I’d like to go out for a drink because they’d like to say thank you and we went to the pub and I had a very, very good time. There was the foreman and John Friel and some other men who’d been in the tunnel.

‘It didn't feel particularly heroic’

I did have to take a deep breath to go down the hole, but I had a very nice fireman helping me in whom I had great confidence and it didn’t feel heroic, it felt as if it was something that needed to be done.

In some ways you dissociate yourself from the day-to-day feelings about these incidents and you’re assembling in your mind what you need to do clinically… feelings about being brave or anxious or all of the rest of it are pushed out by these very practical things; what do I need to think about? What do I need to ask about?

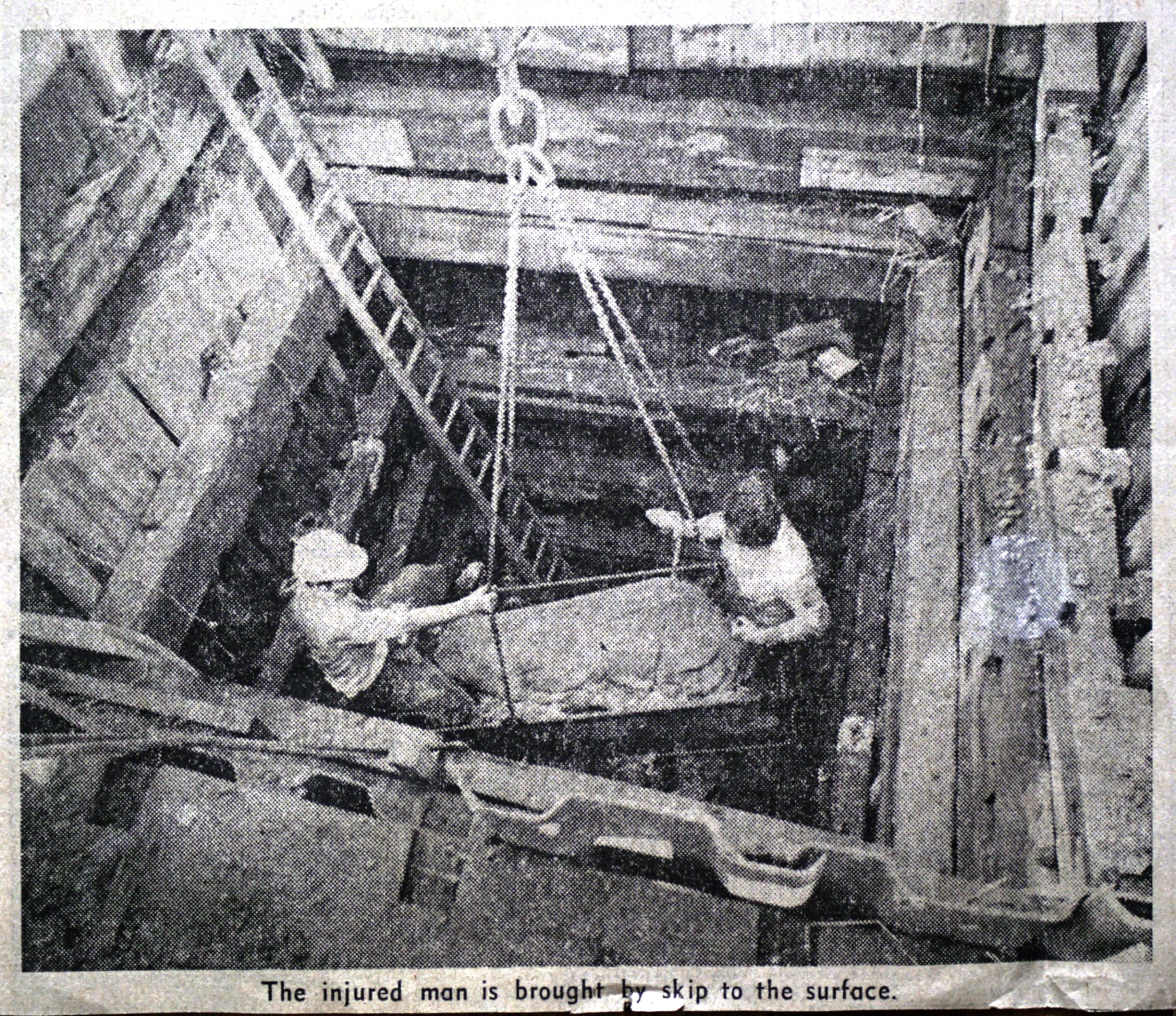

In the immediate aftermath of the incident there was significant press coverage

This came to the attention of the BMA and officials began the process of nominating Dr Butler for inclusion in the Book of Valour.

Unsurprisingly, following such bravery and calmness while working under dangerous and difficult conditions, Dr Butler was included in the Book of Valour later that year.

Dr Butler continued to practise in the local area, first as a GP for many years, before becoming a medical director.

At present, she is non-executive director of Bradford District Care Foundation Trust and still very much enjoying her chosen profession.

Submarine disaster

One of the most tragic entries in the BMA’s Book of Valour commemorates the remarkable bravery of Dr Charles Rhodes who lost his life while saving others in the aftermath of one of the UK’s worst peacetime naval accidents.

National Service

Born in 1928, Charles Eric Rhodes was a bright child and a successful student. Upon leaving Wrekin College, Shropshire he went straight to medical school where his cousin remembers meeting up with him during his studies:

‘He was wonderful fun to be with. He was very courteous, he made you feel very important when he was taking you out.’

After qualifying as a doctor, Charles looked to complete his National Service in the Navy, joining up in 1953 aged 25.

He became Surgeon Lieutenant on the submarine support ship HMS Maidstone based at Portland, Dorset.

By June 1955 he had met and married Jo, a nurse, and was the proud father of a three-week-old daughter, Gill.

Experimental torpedoes

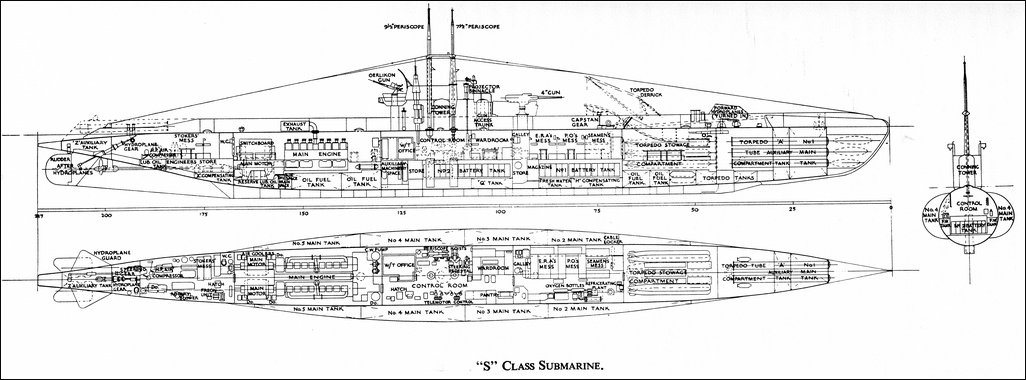

On the morning of 16 June 1955, the Royal Navy submarine HMS Sidon was moored alongside HMS Maidstone in Portland Harbour, with Dr Rhodes performing his normal duties on the depot ship.

Aboard the submarine, alongside its crew of 56, were two experimental torpedoes, codenamed ‘Fancy’, that had been loaded onto the vessel for testing.

At 08:25 one of the Fancy torpedoes exploded, causing catastrophic damage to HMS Sidon. The torpedo tube into which the torpedo had been loaded burst and the two forward-most watertight bulkheads were ruptured.

Fire, smoke and toxic gases quickly filled the ailing submarine.

Twelve men in the forward compartments died instantly and seven others were seriously injured.

The stricken vessel started to settle by the bows with a list to starboard and her commanding officer ordered its evacuation.

Meanwhile, on HMS Maidstone, Dr Rhodes had heard the explosion while having breakfast and immediately rushed to investigate.

Surgeon Lieutenant Rhodes was among the first to enter HMS Sidon and, despite the dense smoke and near total darkness he succeeded in bringing an injured man to safety.

Flying in the face of the obvious danger, Dr Rhodes put on an escape apparatus and re-entered the submarine to give further help to the injured. In doing so he greatly limited his own chance of escape.

Although he had significant naval experience, Dr Rhodes was not a submarine officer. This meant he was unfamiliar with the breathing equipment and did not know the layout of the vessel.

Despite these handicaps, he did not hesitate in returning to the dark and dangerous conditions on the sinking submarine. He succeeded in helping two more men to safety before HMS Sidon sank to the bottom of the harbour less

than an hour after the initial explosion.

Tragically, his selfless and gallant act would cost him his own life.

Tragic accident

Dr Rhodes’ cousin didn’t hear about the accident until later that night:

‘We put on the late-night news and it said this submarine has sunk in Portland harbour and several people have lost their lives. I realised it was Eric immediately. You don’t expect these things in peacetime do you? An accident is an accident but it’s still a horrible, horrible shock.’

One week later, when the submarine was raised, Dr Rhodes was found at the foot of the conning tower. He had suffocated, undoubtedly due to the fact he had not been trained in the use of the escape apparatus and would not have known how

to open the oxygen valve.

The bodies of the 13 casualties were removed from the wreck and buried with full honours in the Portland Royal Naval Cemetery that overlooks the harbour.

The submarine accident received extensive news coverage at the time and the bravery of Dr Rhodes was highly praised and publicised.

He was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal for gallantry and saving life at sea, which provided some measure of comfort to his young family.

A court of inquiry would later clear anyone aboard HMS Sidon for the loss of the boat and the direct cause of the accident was determined to have been a malfunctioning of the ‘Fancy’ torpedo. The torpedo programme

was soon after terminated and the torpedoes taken out of use by 1959.

HMS Sidon itself was subsequently re-floated and then sunk again to act as a sonar target.

Dr Rhodes’ act of selflessness and self-sacrifice would become the second entry in the BMA’s Book of Valour.

On the 50th anniversary of the accident, the Dorset Branch of the Submariners Association erected a memorial stone to those who died, which is situated adjacent to the war memorial at Portland.

Doctors have always put their lives on the line for their patients

The BMA's Book of Valour continues to document the extraordinary deeds of our profession.

The most recent entry is from 2017 and we can be certain that – with medical professionals who pride themselves on putting patients first – it won't be the last.

You can read more entries from the BMA's Book of Valour on our website

here.

Further information

The BBC has an interesting page on Dr Rhodes

here.

More details on HMS Sidon and the disaster can be found

here and

here.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr Susan Butler for being so generous with her time in speaking to us.