Abu works 11 hours a day, six days a week, in a small roadside workshop in Sialkot, Pakistan. He is seven years old.

Abu is one of many children who work in unregulated factories

He is paid 4,000 rupees a month, about £25, to make surgical instruments on a grinding wheel.

He doesn't go to school because his family cannot afford to send him.

Abu's father also works in the workshop, as does his 10-year-old brother. When his uncle died unexpectedly, leaving a large family debt that must be paid, Abu's father could see no other option but to send his two eldest sons to work.

Abu going home after work

Despite child labour being criminalised by national law, an estimated 3.6 million children under the age of 14 work in Pakistan, mostly in exploitative and hazardous workplaces.

Although standards have been introduced to ensure that these manufacturers do not supply NHS hospitals in the UK, child labour still occurs in small, unregulated workshops.

In this region of Pakistan, surgical instrument manufacturing is an established industry, producing more than 150 million surgical instruments a year, with a global market value of over £200 million.

Children at work in an unregulated workshop making surgical tools

In the regulated factories of Sialkot, there are an estimated 50,000 manual workers in the surgical instrument industry, with a typical labourer earning £1.40 a day - that's for a 12 hour work day, often seven days a week.

This isn't ethical trade, but what is being done to tackle it?

Over 3,000 miles away from the heat and noise of the factories in Sialkot, those same instruments are used every day in medical procedures in the UK.

There is little awareness of the working conditions of the people who make surgical instruments

Operating theatres consume the most medical supplies within a hospital, accounting for a third of all hospital supply costs.

But when it comes to the procurement of these supplies into the NHS, value for money is a key concern, with little awareness of the working conditions of the people who make them - up until recently.

Ethical trade is a top-down approach that refers to the steps that buyers, such as hospitals, take to improve the conditions of those involved in the supply of goods and services. The focus is on continuous improvement over time.

While campaigns for fair and ethical trade of coffee, chocolate and clothing are established in the public consciousness, the same scrutiny is not applied to commodities used in the UK healthcare sector.

Outsourcing the manufacture of surgical instruments to low to middle income countries can help boost local economies, but the pressure to produce materials at the lowest cost can put vulnerable workers at risk of labour rights abuses.

In 2007, the BMA Medical Fair and Ethical Trade Group visited factories in Sialkot, revealing some of the unethical working conditions in the manufacture of medical goods routinely used in UK hospitals.

This led to the publication of Ethical Procurement for Health Workbook, a guidance and training resource for procurement staff, produced with the Ethical Trading Initiative and in partnership with the UK Department of Health.

Ethical trade aims to make international business work better for poor and disadvantaged people

This workbook is unique in that it is relevant to all healthcare procurement systems, and accessible anywhere in the world.

It highlights that ethical trade aims to make international business work better for poor and disadvantaged people and encompasses many rights such as working hours, health and safety and wages.

Ethical trade is a model that asks purchasers to systematically assess the risk of labour rights abuses in the goods they procure, and to push for improvement where necessary.

This includes working with companies throughout the supply chain to help workers exercise fundamental rights such as the right to safe and decent working conditions.

‘Ethical purchasing doesn't have to mean more expensive nor does it mean compromising on quality’

The BMA has worked closely with NHS providers since 2007 to support them in introducing social criteria.

This includes securing a commitment from NHS Supply Chain, the largest procurement hub for goods for NHS England, and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

NHS Supply Chain procures around £2bn worth of goods a year, which is about 40 per cent of the total NHS spend on goods in England.

More recently, NHS Supply Chain has introduced criteria on ethical purchasing within its surgical instruments framework agreements, to address labour standards management, and leverage its buying power and supplier relationships to be a force for change.

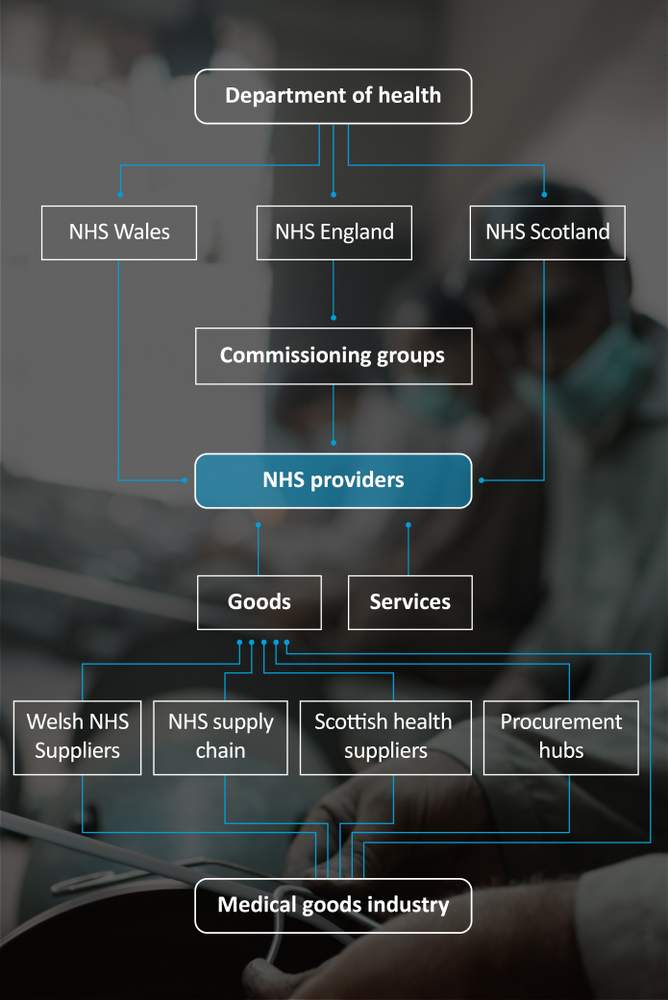

How medical goods are supplied and distributed to the NHS

This system, called the LSAS (Labour Standards Assurance System), places the responsibility on suppliers to demonstrate they have effective systems in place to manage labour standards across their supply chain.

It means successful suppliers are required to undergo a third party audit, at their own expense, and demonstrate incremental progress in achieving milestones.

At a deeper level, it also places the onus on UK companies that source their goods globally, to be responsible about their procurement processes.

NHS Supply Chain is currently developing an LSAS assurance flag that will indicate supplier achievement in this area.

‘Instruments used to heal people have a potentially detrimental impact on the health of people who manufacture them and that is not OK,’ says Alexandra Hammond, associate director of Sustainability at Essentia, Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust.

‘We wanted to do something about the problem; not just acknowledge it and walk away. Our trust appreciates the importance of taking a stance others can take a lead from.’

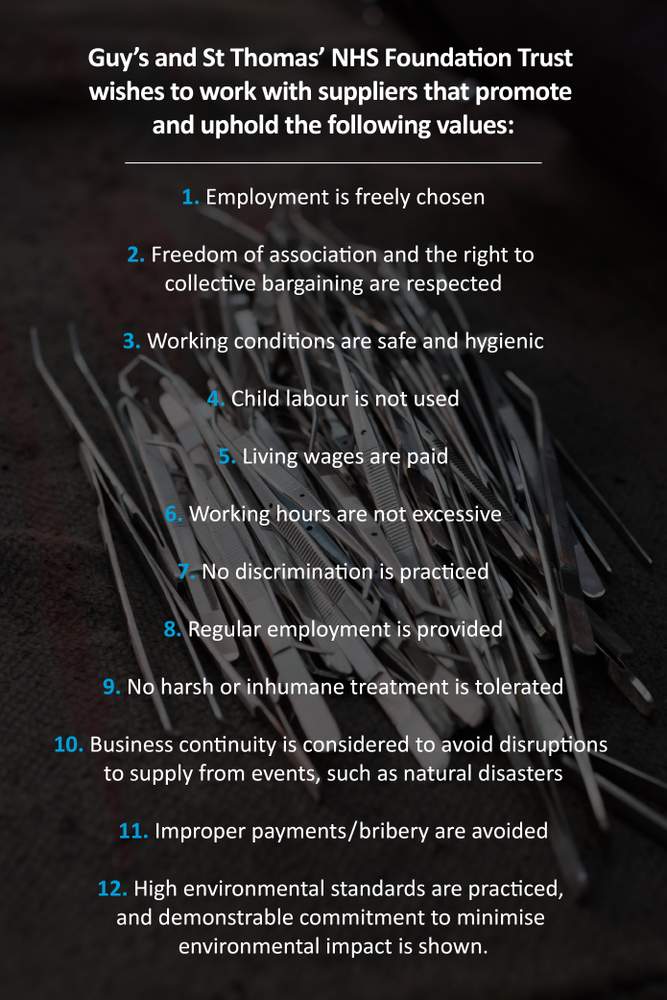

Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust suppliers' code of conduct

‘Other trusts often want to know which suppliers to avoid. But it’s complicated. Even if the conditions are not safe, to break off with a supplier can leave workers in a worse condition.’

‘Many of the suppliers are supporting local economies, whether they are doing things the right way or not. To say ‘get rid of them’ especially at scale, can be a careless move. We didn't want to pull the rug out from anyone without understanding the wider implications.’

Ms Hammond explains that when work is put out to tender by Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, they include their ethical procurement code of conduct.

In October 2014, seven years after its initial visit, the BMA returned to Pakistan to see if working conditions and the level of labour rights had improved following the inclusion of social criteria in procurement contracts in the UK.

‘The management listens to us. We do not have to fight with them’

The four factories visited gave an overall impression of having provided employees with clean working environments and making working conditions and labour rights a priority. The workers interviewed also seemed satisfied with their jobs.

At Sahil Surgical one worker, Ali Rashid, said: ‘I have friends working at other factories, this one is special. Ours is better.’

Haqi Abbas, another labourer, said: ‘The management listens to us. We do not have to fight with them.’

In one of the factories visited, senior management had introduced measures to provide medical treatment when needed, started contributing to pension funds, as well as social security plans for their employees.

They were also offering financial support to cover the cost of weddings and home renovations.

Three of the four factories paid the tuition fees of employees' children

Other improvements across the range of factories included the offer of seasonal food grains at a fixed price throughout the year, subsidised residential housing for six employees through a lottery system, and free lunches.

Huge improvements have been made, however much remains to be done to improve working conditions in the healthcare goods industry as a whole.

‘Dedicated resource is required at a strategic level to develop this further, but each and every trust can take action by adopting the code of conduct and talking about these issues with their supply chain,’ says Ms Hammond.

In England, there are 165 hospital trusts with a spend of over £4.6bn a year on the procurement of medical supplies and other types of consumable goods, purchased from thousands of supplier companies.

‘Each trust can take action by adopting the code of conduct and talking about these issues with their supply chain’

Hospital trusts in England have the freedom to decide what medical goods they buy and how they go about doing so, with minimal intervention or direction from central government.

However a more centralised approach could lead to coordinated purchasing decisions, which could result in more ethical purchasing.

It's clear then that the healthcare sector, with its huge purchasing power, has the capability to improve conditions for workers around the world.

However, bringing long-term change to a global industry worth millions is a huge challenge, requiring sustained effort from a number of bodies.

The BMA's long-term vision is to ensure the NHS is purchasing all medical supplies ethically

In September 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Goals were announced, highlighting public procurement as one of many key drivers for sustainable development, and providing a clear opportunity for health professionals worldwide to bring about change.

The BMA's long-term vision is to ensure the NHS is purchasing all medical supplies ethically.

Our imperative is to continue to work with NHS providers, end users, and suppliers to ensure that sustainable gains are achieved throughout the industry.

What can I do?

See how the BMA can support you to take action at your trust to implement ethical trade for medical goods.

We've also released a new report on the manufacturing of medical gloves. Read our findings and recommendations.

Credits

Writer, digital producer: Emma Lindsey

Sub-editors: Jackie Mehlmann-Wicks, Arthy Santhakumar, Kelly Spring

Senior digital producer: Karen Lobban

Senior designer: Tim Grant

Photographs and videos: Vilhelm Stokstad/Kontinent, i-stock

Many thanks to NHS Supply Chain and Alexandra Hammond at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust for their time and contributions.