Neil Armstrong’s doctor

An interview with the medic behind Apollo 11

When Neil Armstrong’s crew returned to earth, it was flight surgeon Bill Carpentier who looked after them. Fifty years on, he tells us about his weeks quarantined with the moonwalkers, his arduous training for the job, and his determination to make space safer for future astronauts.

Every time Bill Carpentier looks at the Moon, he thinks of the men who fell to Earth and how he cared for them.

Dr Carpentier had perhaps the best medical job of the 1960s.

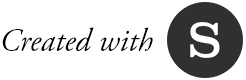

As the flight surgeon for Apollo 11, he looked after Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins before they embarked and, 50 years ago this month, he waited with an anxious world for their return.

Former NASA public affairs officer Jack King announces the launch of Apollo 11, 16 July 1969

Now 83, and speaking from his native Canada, Dr Carpentier tells the BMA of his sense of adventure, wonder and purpose.

While involved with several missions, including the desperate, ingenious and successful bid to save the crew of Apollo 13, it’s the one under Armstrong’s command that is closest to his heart, not just because it was the first to land men on the Moon but because of the three weeks he spent quarantined with the crew when they landed.

‘I cannot look at the Moon without thinking, I knew those guys. There were 12 guys who walked on the Moon, I knew them. What a time to be alive.’

A leap of faith

His job at NASA was the epitome of modernity but he was prepared for it by a childhood which could have been from a previous century. He swam in lakes, jumping off bridges into the water, finding all the fun there was to be had in a small town in western Canada in the late 1940s.

Robust and adventurous, he worked on ships during his summer holidays from college and gained his pilot’s licence. Following a medical degree at the University of British Columbia, he took a three-year residency in aviation medicine at Ohio State University.

It included a third-year work placement, usually in manufacturing or for an airline, but NASA had recently become part of the scheme and took him on for six months at the Manned Space Center in Houston, Texas.

Aerial view of the Manned Space Center in Houston, Texas, 1966

Aerial view of the Manned Space Center in Houston, Texas, 1966

This far from guaranteed a job. Counting against him was the fact that, as a non-US exchange student, the immigration rules said he had to return home and wait for two years before he could apply for a green card.

There’s an exasperated saying when confronted by petty obstructions of a bureaucratic nature: ‘But they can put a man on the Moon…’ To the agency that actually did just that, the US immigration rules were not a hurdle.

Dr Carpentier was hired.

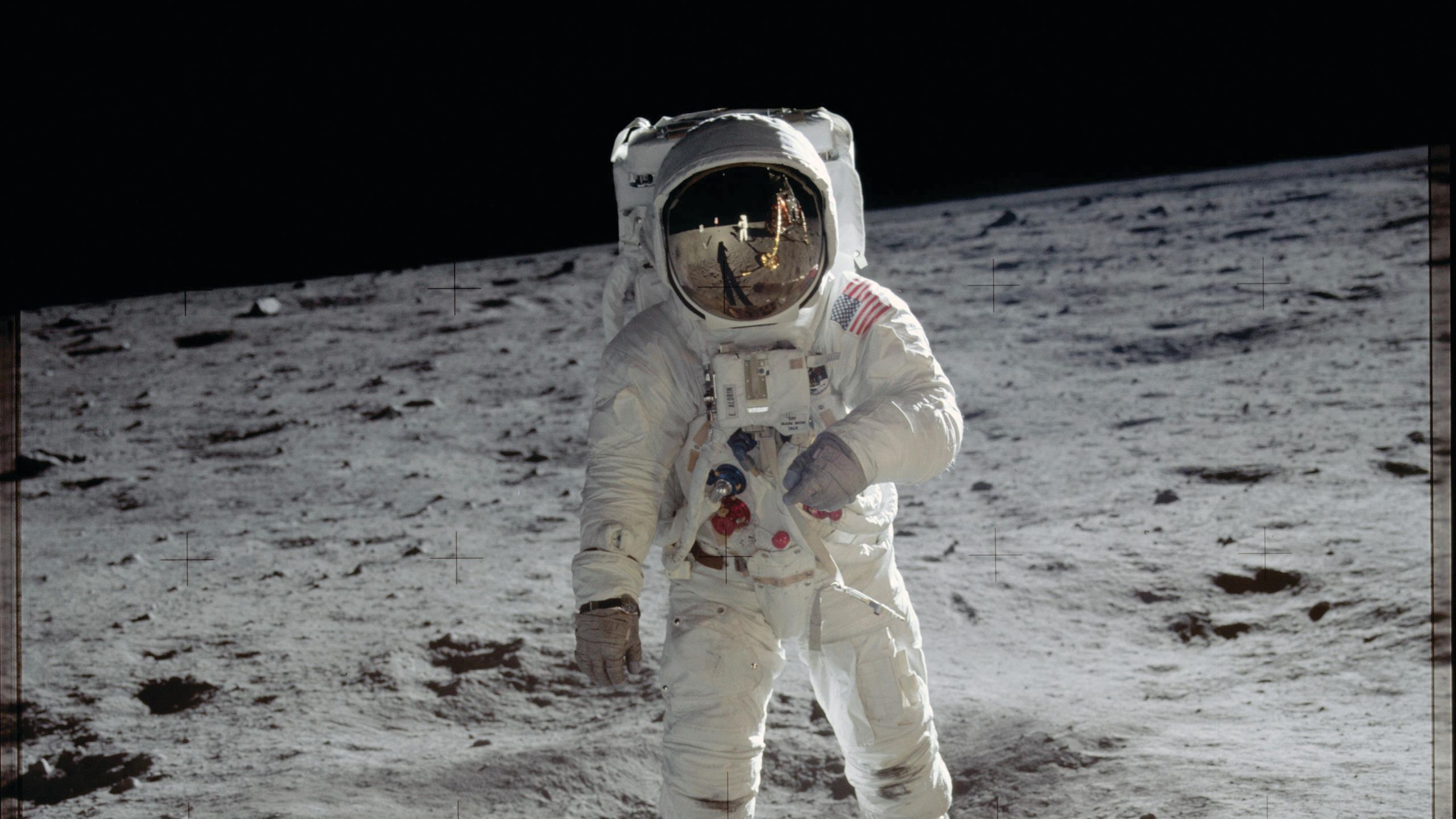

He had kept up with his swimming at college, and had taken scuba diving lessons, and it all helped. As well as the physiological testing and analysis of the astronauts, he needed to train for the recovery of astronauts from the sea.

Dr Carpentier jumps into the sea during training

Dr Carpentier jumps into the sea during training

The rescues were carried out with the US Navy’s UDT (Underwater Demolition Team), the precursor to the SEAL special forces. He heard they were expected to jump out of a helicopter at 20 to 40 knots (23 to 45 mph) from 40 feet, so trained to do the same, with only a wetsuit jacket for flotation.

He recalls the ‘bang’ as he hit the water.

Only later did a UDT officer tell him no, he had been misinformed: this was not standard procedure.

In the water, he practised carrying out CPR on a pliable raft in a high swell. Difficult, yes, but ‘we just kept working at it until we found the best way to do it’. Fortunately, he never had to do it for real.

Just before dawn on the morning of 24 July, 1969, he was on board the USS Hornet, a Second World War-era aircraft carrier, as was President Nixon.

As the module containing the astronauts headed to its splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, Dr Carpentier was dispatched on one of four helicopters.

Thumbs up

The astronauts were winched up, and Dr Carpentier helped them out of the recovery net into the helicopter.

‘We didn’t exchange words,’ he says. ‘They were in biological isolation suits, the helicopter was very noisy, they were on respirators. We had hand signals – “are you OK?”.’

‘One by one they came up. I got a thumbs up from all three of them. My life was complete.’

Once on board, he and project engineer John Hirasaki followed them into a converted Airstream trailer where they spent the first three days of quarantine, before they were flown to more spacious facilities in Houston.

Some people, in close confinement with three global heroes just back from the Moon, would have driven them mad with questions. But Dr Carpentier was not there to talk about small steps and giant leaps. Apart from the odd stint as a bartender, he was busy with his work.

‘I tried to do everything in the trailer that we were doing pre- and post-flight. To get the data to understand changes in physiology that were happening… it was what we could learn. We had to learn because we wanted to keep doing this.’

His responsibility was enormous, not just for the individual astronauts but that the system of quarantine was successful.

Dr Carpentier (left) tests quarantine elements prior to the Apollo 11 mission

Dr Carpentier (left) tests quarantine elements prior to the Apollo 11 mission

The idea of there being life somewhere other than on Earth is profound but the immediate need was not to philosophise but to protect the Earth from possible harmful lunar microbes.

‘The possibility of life existing as we knew it was difficult to contemplate, but you could not say it was zero. Maybe just a short distance below the surface of the Moon there may have been something harmful, so when you took that incredibly small possibility and multiplied it by the Earth’s population, it became a significant number. It was important to do what could be done to protect the biosphere.

‘We had to make sure everything was done to plan, because [if not] the whole aircraft carrier, including the president, could be quarantined.’

For all mankind

Fifty years on, you still get a sense of Dr Carpentier’s sense of duty and discipline. Rarely at the time did he dwell on the historical significance of his work.

Constantly, the thought was ‘don’t mess up’. NASA entrusted young employees with enormous responsibility – he was 33, and the average age in the control room when Apollo 11 splashed down is said to have been 28.

‘There was a job that needed to be done. You were asked if you could do that job, and if you said yes, you did whatever it took to make sure that you could do it,’ he says.

He points out that when John F Kennedy said the USA would put men on the Moon by the end of the 1960s, there were two parts to that promise – to get them there, and bring them safely back.

‘The second part was where I got involved. To evaluate these guys when they returned to Earth.’

The austere surroundings of quarantine were followed by a lavish ‘Giant Leap’ world tour as Dr Carpentier and the crew met presidents, prime ministers and the Pope. He recalls Neil Armstrong’s diplomatic skill and facility with languages.

‘Everywhere we stopped there was an incredible reception. There was never a negative comment. The plaque that was left on the lunar landing module – “we came in peace for all mankind” – that was the attitude. It was an incredible achievement and it was done in this spirit for all mankind.’

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew in a ticker tape parade down Broadway and Park Avenue

New York City welcomes the Apollo 11 crew in a ticker tape parade

By the time Dr Carpentier returned from his tour, Apollo 13 was about to set off. A different doctor had been assigned as flight surgeon but Dr Carpentier was asked to help out as staff support to the Mission Operations Team in Mission Control.

What followed was a technical achievement in some ways even greater than the first Moon landing.

An oxygen tank exploded, crippling part of the craft. The crew had limited power, loss of cabin heat, a shortage of potable water and needed to carry out makeshift repairs to the carbon dioxide removal system.

Dr Carpentier stresses that it was the engineers who were the heroes, improvising a solution. His job, however, was vitally important, calculating the effects rising carbon dioxide levels would have on the crew.

Astronauts John Swigert, Fred Haise and James Lovell climb to safety after the failed Apollo 13 lunar landing mission

The Apollo 13 astronauts John Swigert, Fred Haise and James Lovell climb to safety

He remembers the intense anxiety he felt as the capsule returned to Earth, and the huge cheer from mission control as communications were re-established. Watching the film version, starring Tom Hanks, decades later, his instinct was to leap up once again and cheer.

One planet. One human race

For his work on Apollo 13, Dr Carpentier was included in the Mission Operations Team that was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After the Apollo programme finished in 1972, Dr Carpentier took a university residency and then pursued a successful second career in nuclear medicine for the next 30 years.

Dr Carpentier with his wife Wilma, having received an honorary doctorate last month from the University of British Columbia Okanagan

Dr Carpentier with his wife Wilma, having received an honorary doctorate from the University of British Columbia Okanagan

He returned to the USS Hornet, which is now a museum, to pay tribute to Neil Armstrong when he died in 2012. But his involvement with NASA was much more than a matter of attending funerals and reunions.

His determination to make space travel safer never left him.

He is writing a book to gather together the medical data on the American space programmes from Alan Shepard’s first flight in 1961, through Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab.

‘It cost millions of dollars and thousands of man hours to acquire and it needs to be used,’ he says.

Some of the data was in boxes in his garage – he has always been a bit of a hoarder, and is grateful for that now.

It may seem strange that it has not been collated previously, but stringent privacy rules meant that health data could not be published about an identifiable astronaut without their permission. Dr Carpentier has written to all the surviving astronauts from the programmes to obtain it.

‘Almost all of the data that has been published in papers and books are about specific systems – a chapter on the cardiovascular system, another on the pulmonary system, the nervous system. But it has not all been available to integrate.

‘But you’re not sending a cardiovascular system into space, you’re sending a person. The data needs to be integrated to understand that.’

In caring for future astronauts, Dr Carpentier also cares about the future in space.

Fuelled by Apollo euphoria and unaware of impending funding cuts, NASA was speaking of a manned mission to Mars by 1982.

But despite numerous presidents promising to revive the ambition, the prospect seems distant. The Moon walks seemed to offer the future of permanent settlement but instead seem like three short and distant years of wonder.

‘If someone asked, do we need to go back to the Moon, I’d say you bet. Further exploration, going to Mars, doing all of these things, understanding human physiology. We need to keep learning new things,’ he says.

When it comes to what space has taught him, perhaps the most profound lesson speaks to the humanity that drives all doctors in their work.

He quotes Stephen Hawking:

‘When we see the Earth from space, we see ourselves as a whole. We see the unity and not the divisions. It is such a simple image with a compelling message. One planet. One human race.’

Story by Neil Hallows

This article first appeared in the July 2019 edition of The Doctor