‘People like us don’t become doctors’

Overcoming the toughest social barriers to enter medicine, doctors and medical students tell us how they made it against the odds

‘People like me don’t become doctors.’

For most of her life, these six words have governed Laura McManus’s view of herself and how her future would unfold.

From an early age, the now 31-year-old had aspirations of studying medicine, yet a combination of the pressures in her personal life, discrimination, socio-economic surroundings and the attitudes of those around her, made her dream seem an impossibility.

Now a foundation year one doctor, Dr McManus’s journey into medicine was not only unconventional but saw her having to overcome personal circumstances and a start in life that to many would have seemed insurmountable.

Growing up in Preston, she lost her mother at the age of three and ended up living with her father in a one-bedroom flat on a council estate.

Her ambition to become a doctor began as a young girl worrying about the health of her father, who has hydrocephalus.

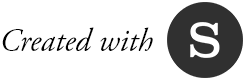

Laura with her dad

Laura with her dad

‘When I was very young, he would get headaches all the time, so I used to want to be a brain surgeon to fix him, but it became apparent that things like that don’t happen to people from my background,’ she says.

‘When you come from a background of extreme poverty, you face discrimination at every turn, it’s pandemic. Teachers wrote us off as “bad kids” that would never achieve anything.

‘They would literally laugh at the idea of me becoming a doctor.’

One well-meaning adult, hearing her career plans, suggested she should become a hairdresser instead.

Dr McManus explains that she didn’t have the same educational experience as other children, and through frustration at the system, and dealing with difficult situations at home, she ultimately played up to that image.

It was this that led to Dr McManus being permanently excluded from school at the age of 15 owing to poor behaviour and attendance.

‘It wasn’t that I was academically incapable, it was discrimination and the lack of support, resources and self-belief.’

Her situation was further complicated when, at 16, she became pregnant, leading to her leaving her family home and spending 18 months living in homeless hostels.

She describes the relationship with her son’s father as ‘volatile’, and at 19, she ended the relationship and became a single parent.

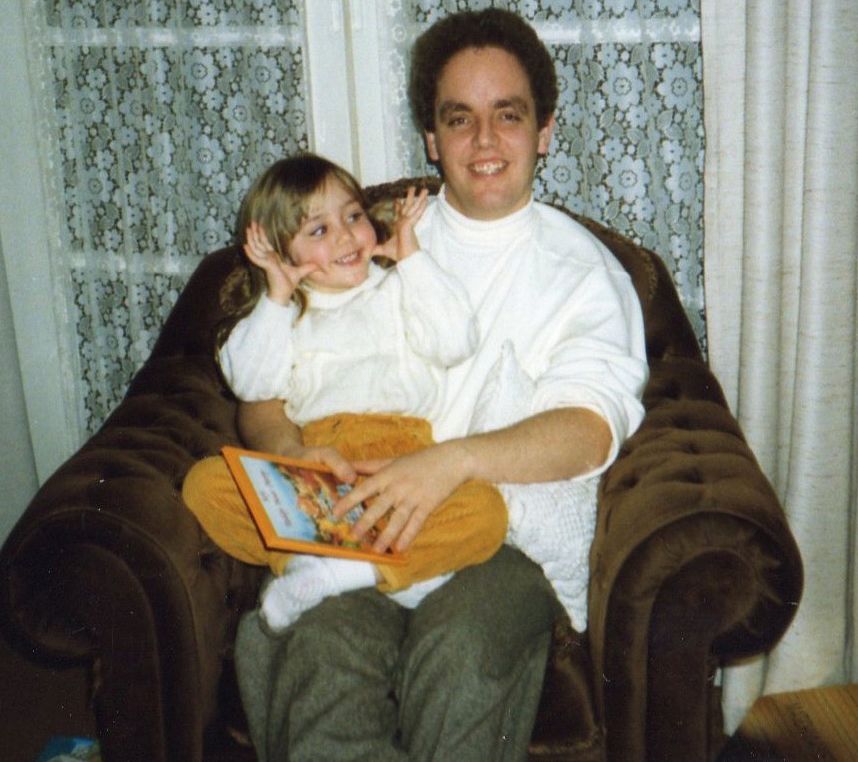

Laura with her newborn son Byron

Laura with her newborn son Byron

It was then, after doing a succession of jobs such as cleaning, serving in a chip shop and care work, she began to think ‘there must be more than this, I want to give my son something better than I’ve ever had’.

She began to google science degrees; the idea of becoming a doctor still seemed out of reach. This is where she first learned about A-levels.

‘School had never informed me about A-levels and I had not known anyone to do them in my personal life, I just didn’t know they existed.’

After approaching a local college, she was able to convince staff to allow her to take A-levels in chemistry, biology and maths, despite not having the required GCSE results.

After excelling in her AS year, she was asked by her biology teacher what she wanted to do in the future and mentioned dismissively how she had, as a child, wanted to become a doctor.

‘I told her the idea of me being a doctor and she just said, “well why not?”. That made me suddenly ask myself the same question.’

With the support from course tutors, Dr McManus approached local universities explaining that she wanted to study medicine but did not have the requisite GCSE results. Two universities responded and, after some negotiation, it was agreed that she could be admitted to their medical course provided she achieved five GCSEs and another AS level in addition to the A-levels.

This led to another hurdle – as a mature student only maths and English GCSEs were available through her local colleges, so Dr McManus had to learn the curriculum herself and find a high school to allow her to sit the GCSE exams as a private candidate.

In 2014 she finally secured a place to study medicine at Lancaster University. Learning that she would be able to attend university to study medicine was an amazing yet surreal moment in her life, she says. It was not without its challenges, however; she faced eviction, had a breast cancer scare and lost several family members.

‘I didn’t have the same family situation or financial security as other students and had to use food banks several times throughout medical school. I suffered great anxiety early on as I struggled to “fit in” with students from more affluent backgrounds.

‘My vocabulary was very limited compared to others and I found myself frequently not understanding teaching and conversations purely because of the vocabulary difference.

‘I felt I had missed out on the hidden curriculum of being middle class, which seems essential for studying medicine.’

Despite these difficulties, with the support of Lancaster Medical School, Dr McManus has now completed her studies and is working in her hometown at the Royal Preston Hospital.

Laura graduating from medical school with her dad, godmother and son

Laura graduating from medical school with her dad, godmother and son

Looking back over the obstacles Dr McManus has had to overcome and how things can be made easier for future prospective doctors, she says: ‘I would like to highlight the inequalities of people from my background and hopefully inspire someone to dream big and go for it, even when you feel the world is against you and that things can’t improve.

‘When I see people from my childhood, I am constantly told, “you must be really clever, I could never do anything like that, I’m just not clever enough”.

‘But it could not be further from the truth.

‘It’s just they haven’t had the same opportunities or support and instead, they have faced multiple hardships and faced discrimination at every turn in their lives.

‘They are clever enough and they are capable, if they are given the right support and the self-belief that they are able and deserving of achieving more, they can achieve whatever they want.’

As a career, medicine has for a long time been seen as the preserve of the financially and academically privileged, with statistics often lending weight to this perception.

While just 7 per cent of the UK population attended independent schools, those students made up 61 per cent of the total entrants to medicine, according to a 2016 report by the Sutton Trust on the educational backgrounds of UK professionals.

In an effort to improve diversity of medical school candidates, the trust has called on universities to ‘contextualise admissions to study medicine, recognising that academic ability is just one crucial part of being a successful doctor’.

It has also called on schools and medical colleges to collaborate to encourage pupils to take an interest in medicine and increase students’ exposure to the possibility of studying medicine at an earlier stage in their education.

Improving the aspirations of students from educational and social backgrounds under-represented in medicine, and ensuring they have equality of access to medical school, are known respectively as widening participation and widening access.

Dr McManus feels that, although she didn’t benefit from widening participation, her journey would have been made easier if that support were available to her.

She believes that widening participation is crucial to support people into medicine – but also believes that for people of her background, many of the existing initiatives are too limited to work well.

‘Widening participation needs to be targeting people from a very young age and targeting mature students. By the time people turn 18, it is likely too late to make many real differences as they are likely falling into similar situations I have faced, not achieved well at school and not even considering university as a life option.

‘Like myself, it may take several years longer for life to settle down and to be in a stable enough situation to be able to plan for a career, rather than worrying about whether to spend the last few pounds on food or electricity.’

‘That is why I believe targeting people in primary school or high school starters would be more effective, or targeting people attending college as a mature student when they are ready to plan for a different future.’

Dr McManus feels people like her – who have managed to make it in medicine against the odds – have a responsibility to share their stories and make themselves visible in order to inspire and encourage others from disadvantaged backgrounds to consider becoming doctors.

‘There are a lot of people out there who have the skills but aren’t channelled in the right way or have all their options presented to them.’

Kinan

A sceptical ambition

Twenty-year-old Kinan Wihba was just a teenager when he came to the UK in 2016 with no UK qualifications and limited English skills.

Despite the harsh realities of his early life, he is now studying medicine at Imperial College London and hopes to one day specialise in obs and gynae.

‘I really like the field because you get to care for two patients at once and [the birth] is a very special memory for the family and you get to be a part of that.’

The fact that Kinan is in the position to realise such an ambition is as astounding as it is to be celebrated.

Born in Syria, Kinan was six when he first had dreams of becoming a doctor.

As he grew older, this ambition remained undiminished; even as his home country began to be engulfed in the unfolding chaos and destruction of a civil war.

‘At the start of the [Syrian] civil war I was a child living in a town about 20 minutes away from Damascus,’ he says.

‘The first two years of the war, although there were a lot of troubles in other cities, there wasn’t anything happening in my town, so it felt relatively safe.’

In what was later described by the Syrian state as a terrorist attack, a group of people attacked key buildings in Kinan’s town, resulting in a number of people being killed.

‘Then came the summer in about 2013 or 2014 when the town’s police station and city hall were blown up and things were never the same after that,’ Kinan recalls.

‘The military came into my town and just never left. After that we didn’t get to go to school for a while, and even when we [eventually] went to school, it was on the basis of how safe it was to go.’

‘It was a case of either risking it by going to school or just staying at home, and even by staying at home you were not that safe.’

It was around this time that Kinan’s family began to consider the fact that they might have to leave Syria for their safety. In 2015 his mother and elder brother made it to the UK where they sought to claim asylum, a status that was eventually granted to them in March 2016. Just a few months after this decision, Kinan along with his father and younger brother left Syria and flew to the UK, landing at Heathrow.

‘My mother was already in the UK and had already been granted asylum. Because she had children under 18 who were still in Syria and in danger, she was able to apply for a family reunion.’

He remembers the day he arrived in the UK – it was raining of course – and seeing his family members again.

‘I was very happy – obviously it was very overwhelming and we [his family] had our reunion in the airport. I liked the country and my first thoughts were about the sense of safety it gave me and how I didn’t need to be worried about my life.’

Despite the challenges of his new surroundings, Kinan remained as focussed as ever on his plans to study medicine.

He says the lengthy and highly formalised qualification process for medicine had a certain appeal because, to him, it represented stability and certainty, qualities that had largely been absent from much of his early teenage years.

‘I never changed my mind, I always wanted to be a doctor,’ he says.

‘Even before I learned about the practicalities of the job or how to become one, I just knew it was something that I wanted to do.’

‘You know that you will do medical school, then move on to your foundation training and then, hopefully, specialty training,’ he says.

‘When I was living in Syria, I didn’t know what was going to happen on a daily basis and that was very hard to deal with.’

Soon after his arrival in the UK, Kinan relocated to Brighton where his mother and brother were already living, and began making enquiries about attending Cardinal Newman Catholic School in order to take A-levels in maths, biology, chemistry and physics.

Although able to converse in English to a basic standard, Kinan realised that he would need to improve his command of the language if he was to study medicine. He did this partly in his free time watching YouTube tutorials and reading.

He also learned that his Syrian qualifications were unrecognised in the UK, and that he would need to complete GCSEs in maths and English along with his A-levels.

In addition to this Kinan would later also have to complete the BMAT (BioMedical Admissions Test) and UKCAT (UK Clinical Aptitude Test).

‘At that time I had never been told about UCAS or how you applied for medicine,’ he says.

‘I looked at the entry requirements for some of the medical schools and most of them wanted English and Maths [GCSE]. I talked to the head of my year at Cardinal Newman and they re-arranged my timetable so that I was able to sit the exam alongside those doing their re-takes.’

Despite supporting him in his bid to apply for medicine, the college was initially sceptical about the achievability of Kinan’s ambition.

‘They were sceptical because I had just arrived [in the UK] and did not yet speak English fluently,’ he says.

‘They weren’t sure if I’d be able to keep up with my subjects. However, once I had convinced them of how I could prioritise my studies, they supported me all the way.’

He was able to further benefit from a widening participation summer school run by Brighton and Sussex medical school called ‘BrightMed’.

‘It gave a good overview of the process for the application to medicine; the admissions tests and the interviewing styles.

‘It was through this [scheme] that I then heard about a work experience programme co-run by Health Education England and the Royal Society of General Practice, which [in turn] gave me a lot of insight into how primary care worked and what GPs did and was very helpful both for my personal statement and my interviews.’

After securing a conditional offer to study medicine at Imperial, Kinan is now in his second year of study.

He says that while support for students coming from challenging backgrounds exists, more needs to be done to inform and advertise this support to those who might qualify.

‘There is support but I believe that people often aren’t made aware that the support exists,’ he says.

‘For example, through things like contextual admissions your background can be taken into account [when applying to medical school] and making people aware that things like this exist is crucial.’

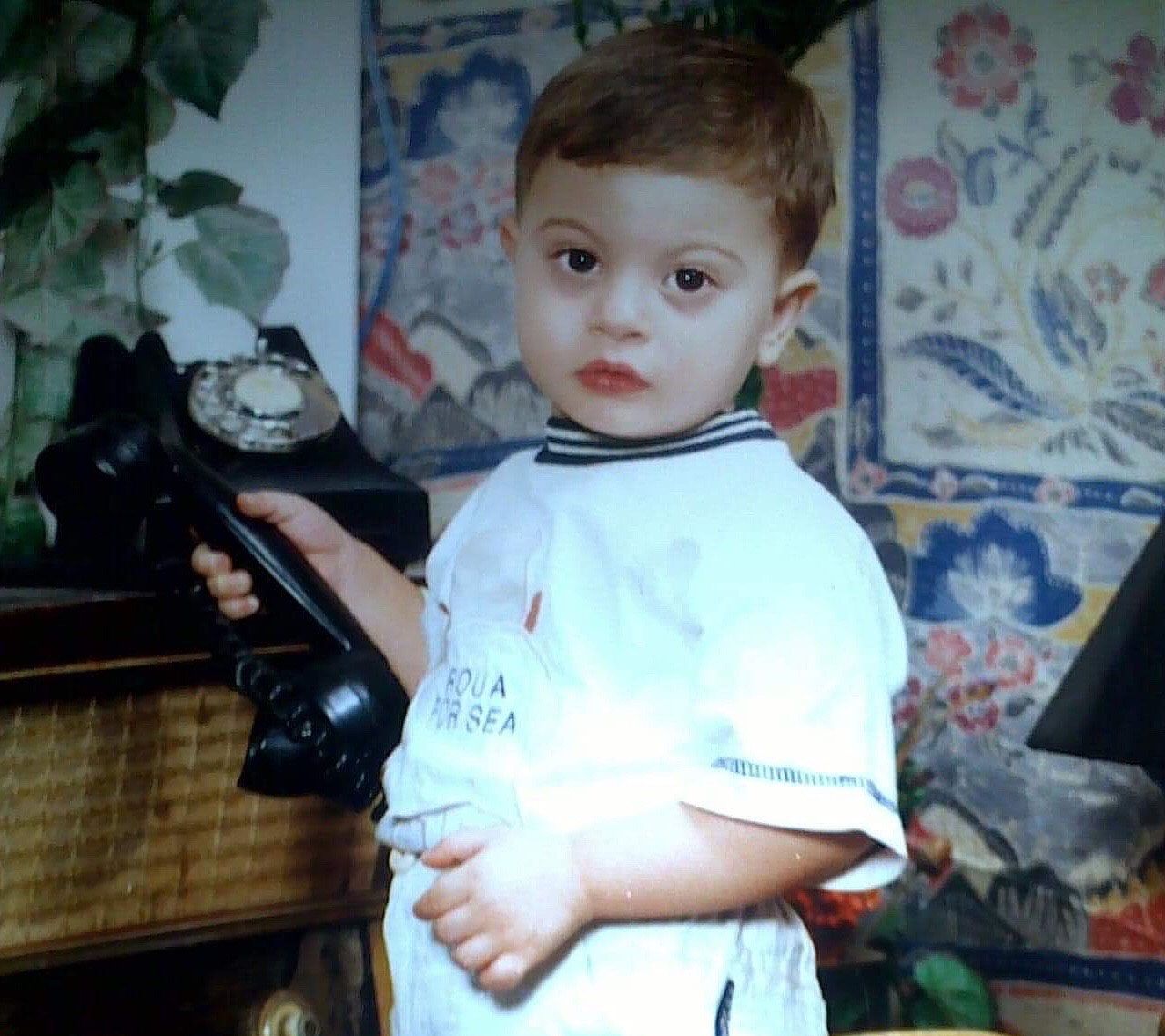

Theodora

Obstacles to applying

Originally from Nigeria, medical student Theodora Okechukwu came to the UK with her family aged eight, settling in Enfield.

Attending a comprehensive school in Barnet she discovered a love for science subjects and decided to become a doctor after one of her teachers suggested it to her.

‘My biology teacher had so much faith in me and really helped. Without that teacher I don’t think I would have got in to medicine,’ she says.

‘Neither of my parents are in the medical profession, so I didn’t have any point of contact; anyone I could speak to to understand the process for applying.’

While private schools and colleges will often host dedicated programmes to assist pupils looking to apply for medical school, such resources were simply not on offer at Theodora’s school.

‘Trying to get through the application process by myself was probably the biggest obstacle I faced,’ she says.

‘Coming into medical school and seeing all these people whose parents were doctors or their school had had a medical school programme that would take them through interviews – I didn’t really have that.’

Six people in her year applied for medicine, with Theodora and one other pupil winning places. Since becoming a medical student, she has sought to help students in a similar position to the one she faced through involvement in e-mentoring schemes and blogging about widening participation on Instagram.

‘You’d be surprised how much just knowing someone who’s been through the process makes such a difference to you applying, and I really want to be that person for as many people as I can,’ she says.

‘I think for some teachers [at my school], they were maybe confused about my hunger to study medicine. My AS level results were not the typical four A’s you’d expect, but I was determined that I would still apply. A lot of people would tell me that there were a lot of other subjects I could apply for with the grades I had.

‘One of my brothers attended a selective school for sixth form, and it’s completely different how students are handled there when they want to pursue something like medicine or law or go to Oxbridge.’

Now in her fourth year at Nottingham University, Theodora says widening participation is not just about increasing equality of opportunity for students, but ensuring that the health service better represents the patients it cares for.

‘If a patient sees someone who they think they can relate to [it] will make them more likely to speak up,’ she says.

‘That’s really important for patient care because if a patient doesn’t feel able to speak up, [as a doctor] you might miss things.’

Christine

A constant battle

Bristol medical student Christine Cadman feels that the personal adversities she has faced could help give her more perspective when she comes to qualify as a doctor.

She decided to pursue medicine aged 19 having spent several years in care and, at age 15, being hospitalised for a number of years owing to her mental health.

She had been able to take her English language and maths GCSEs while still in year nine and while in hospital was able to complete exams in biology, chemistry and physics.

She says she was inspired to go into medicine by one of the doctors she encountered while in treatment.

‘One of my consultants was a lovely man who always said to me: “You’re so clever, you could be a doctor one day,” but at the time I was just not interested,’ she says.

‘When I was getting ready to leave hospital everyone around me was telling me that I needed a goal, and so I decided I was going to try.’ Christine was discharged from hospital at 18, sent to a care home and then on to an education unit where she was told that it wouldn’t be possible for her to study chemistry or biology at A-level.

Through sheer determination she was able to persuade her care home to send her to a college where she could take the necessary subjects.

After completing her A-levels at the age of 20, she secured a place at the University of Bristol and is in her third year. She credits her attendance at widening participation summer schools with her successful application to medical school.

She feels she had had to fight a near constant battle to persuade those around her that she should be given the chance to study medicine. ‘It was constantly “you’re not going to be able to do this” or “you’re not that sort of person”,’ she says. ‘If it was not for my college, who were amazing and did everything they could to help me get there, I probably wouldn’t have gone into medicine.

‘A career in medicine shouldn’t be just for the advantaged. Not everyone has a conventional route into medicine and that’s OK – these struggles can in fact prepare you for the things you will face every day as a doctor.’

Deprived areas

Published last November, the Medical Schools Council’s selection alliance report provides insight into its efforts to improve widening participation.

The report contained some encouraging signs such as the percentage of BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) students entering medicine having risen annually from 28 per cent in 2011 to 41 per cent in 2016.

Less encouraging, however, is the finding that entrants to medicine from the UK’s most deprived areas, as determined by the Index of Multiple Deprivation, have increased by just 5 per cent between 2007 and 2016.

The report also reveals that while 43 per cent of those entering college or university had parents without higher education qualifications, such applicants only made up 23 per cent of entrants to medicine.

Building confidence

Recognising and giving greater support to ‘looked after children’ (children in care) looking to pursue a career in medicine was an issue brought before this year’s BMA annual representative meeting in Belfast.

Initiated by the BMA medical students committee, those at the meeting emphasised how those leaving the care system needed to be viewed as of equal value to the medical profession as other applicants, and should receive additional support and information from universities when applying or interviewing for medical degrees.

It also called on the association to lobby medical schools on the need for specific policies around ‘looked after children’ as a vital means of increasing their participation in the medical profession.

Medical schools in the UK are required to host an outreach scheme aimed at improving access to courses such as medicine. The oldest such course is the EMDP (Extended Medical Degree Programme) at King’s College London, launched in 2001 before such schemes became mandatory.

It was the first widening participation initiative of its kind and despite taking on just 10 students in its first year, now has an annual intake of 77 students, with more than 400 doctors having graduated from the programme since it began.

Aspiring doctors

Inspirational stories helping school students realise their potential, or even just consider medicine as a possible career, is just one objective of the Aspiring Doctors programme.

The programme is looking for medical students and doctors who want to make a difference by visiting schools and colleges and talking about their route into medicine, what challenges they faced and what options exist for those with similar aspirations.

Newly qualified doctor Brooke Davies is one of those looking to get involved.

As the BMA medical students committee widening participation lead Dr Davies led calls for doctors and medical students to share their stories to illustrate the range of backgrounds of people entering medicine, and increase awareness and engagement with widening participation.

Having herself come from a working-class background and being the first member of her family to attend university, she is now an F1 at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary and says that an individual’s background should never serve as an obstacle to them studying medicine.

‘Widening participation, for me, is the concept that allows anyone to have a chance to be a doctor. Your background should not matter,’ she says.

‘It should not matter if you have parents who are doctors, parents who are not, or you don’t have parents. It should not matter if you live on a council estate, live in care or live between homes. It should not matter if you are white or BAME, female or male. It should not matter what your faith is or what you practise. It should not matter that your school was private or your school was a poor performer.

‘It should only matter that you want to study medicine and are willing to work for it.’

Story by Tim Tonkin