Streets of shame

Homelessness and the NHS – a tome of tragedies

For two and a half years Samantha Moss and her partner Clayton Bradshaw slept under the cold, stone arches of Nottingham’s Trent Bridge.

In the shadow of the ballooning wealth of two professional football clubs, on the edge of one of the country’s most well-to-do leafy suburbs, the couple survived ice and snow, witnessing regular criminal acts and abuse, with the wind whipping off the water each and every day.

Wandering through the streets of West Bridgford – where the average house price is more than £330,000 – to the homeless drop-in centre that eventually helped find Samantha and Clayton a home, it is hard to believe such hardship can exist.

But it soon becomes clear that their story is just one chapter in a tome of tragedies.

When 44-year-old Samantha, a mum of five, speaks to The Doctor at the Friary Drop-in Centre – which sits in the heart of the largely Victorian suburb, a single-storey building that has the feel of an old temporary school classroom – it is busy and bustling.

Volunteers with cups of tea and plates of food duck and dive in every direction, piled-up boxes of clothes and food packages seem to reach the ceiling in one corner and 80 or 90 people in varying levels of physical and mental distress – some chatting animatedly, some dabbing at wounds on their legs or slumped with head in hands – occupy chairs and tables, waiting for refreshments or much-needed advice.

Samantha has been one of the luckier of this group in recent years, having been found housing eight years ago, but still returning to the drop-in centre for help, advice and company. But, today, her eyes are full of the sort of worry most people never experience.

‘I am being evicted out of my house in January; my landlord is selling up and we’ve been told we’ve got until then to find somewhere. I’ve been to see housing aid but there’s nothing for us at the moment.’

Clayton, her partner since those days under Trent Bridge, who has depression and anxiety, adds: ‘The landlords all want so much money up front – a grand up front, five hundred quid up front. We’re only on jobseekers allowance. We’d got settled. We’d been in this place for two and a half years so it’s really stressed us out.’

Samantha is warm, chatty and eloquent but can hardly bring herself to recall what life was like in what must seem like a different world, sleeping on streets, in parks and under bridges.

‘It was a long time, it wasn’t nice. You see so many dodgy things. You don’t forget – it stays with you.’

And asked to look to an uncertain future, she says: ‘It doesn’t bear thinking about. The streets are getting worse, too. People are getting robbed and stabbed all the time. There’s more people out there by a lot than what there was and they are having a harder time.’

Clayton adds: ‘I didn’t get much sleep because she [Samantha] is a woman on the streets so I thought I needed to stay awake to protect her. It was horrible. It was stressing all the time. When it was snowing it was the worst. It was so cold.’

Every night there are scores of people in Nottingham alone, facing these sorts of realities. Just a handful of years ago the number of people sleeping rough was in single figures. Now, it’s likely to be dozens.

Brendan O’Connor, another regular user of the Friary, was homeless for 10 and a half years until being found a flat six months ago. ‘You just haven’t got a clue,’ the 49-year-old says when asked what life is like on the streets.

‘I’ve had my head kicked in, I’ve been robbed, I’ve been abused – I could go on about the bad stuff all day. There’s not much I haven’t seen – I’ve seen people I know die.’

These are stories familiar to Ann Bremner, the general manager of the centre, who set up the faith-based service – which provides a GP, food and drink, assistance with administration, IT support and a warm welcome – 30 years ago when West Bridgford was a deprived area, far from the mecca for young professionals with well-paid jobs it is now.

‘People don’t see them as part of the community,’ Ann says. ‘They don’t see them as people like I do. Everyone has had a previous life before coming here, and very interesting ones.

‘There is an “us and them” mentality in society.’

‘There are lots of professional people here too – it doesn’t matter what abilities you have, you can become homeless or you can turn to addiction, and that is just oblivion. Life is valuable and we always believe that people can change or that we can give them hope.’

Ann Bremner has been to 15 funerals in the last year alone.

The number of people sleeping rough, passing between streets and hostels or vulnerably housed, is growing rapidly. And the lives of people like Brendan, Clayton and Samantha represent a health epidemic for the UK.

A bleak picture

New research from The Doctor paints a picture of a society in which homelessness is growing rapidly and the interaction between homeless people and the stretched NHS is soaring.

Our figures – collected through a series of Freedom of Information requests – reveal that the number of recorded visits to England’s A&E departments by patients classed as having no fixed abode has nearly trebled since 2010/11.

In some parts of the country the numbers have risen by five or six times – and at one London hospital trust, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, numbers are 15 times higher now than they were.

Recorded admissions from emergency departments to hospital wards have also rocketed, from 3,378 in 2010/11 to 5,029 in 2017/18.

Each visit to A&E is estimated to cost the NHS around £148, and one day spent in a hospital bed around £400 – meaning these figures alone represent a bill to the NHS of more than £47 million.

The reality is that the true cost to the UK’s hospitals and the NHS will be much, much higher. Not only did a significant number of trusts fail to respond to The Doctor’s request for information, but the NHS also has notoriously poor recording mechanisms for homeless patients. Most simply fall through the cracks, recorded as having an address: a GP surgery, a night shelter, a housing aid centre or a friend’s house.

On top of that, on most occasions homeless patients would spend more than one day in a hospital bed. During days spent meeting experts and homeless people in Nottingham, The Doctor was told a number of stories of homeless patients stuck in hospital beds, even when medically fit, for up to 250 days.

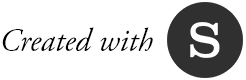

And it’s not just in hospitals where The Doctor has found increased strain on services – and rising demand from a growing population. The Doctor also requested information from the country’s 10 ambulance trusts. Most said they did not record data relating to homeless patients or rough sleepers but two did respond with figures, of varying detail.

Health epidemic

The total cost of homelessness in England was estimated by the Government in 2012 as up to £1bn a year. And these statistics would likely be dwarfed by an updated figure.

Back in Nottinghamshire – a county covered largely by two hospital trusts, Nottingham University Hospitals and Sherwood Forest Hospitals – The Doctor’s figures show that A&E attendances have risen from 542 in 2011/12 to 744 in 2017/18.

Brendan explains why interaction between the health service and homeless patients is so frequent, through his own experience: ‘I was drinking a lot of whisky. I was collapsing all the time and I went up to Holme Pierrepont [a country park in Nottinghamshire] where some people have a caravan and a tent – it had rained a lot, there was water all over the land. I was getting trench foot. I collapsed and eventually I was on a life support machine for months. I woke up with a beard so big on my face I couldn’t recognise me. I was in an induced coma all that time.

‘It has happened quite a bit yeah [having to go to hospital], of course it does. I’ve had trench foot and pneumonia countless times. You just can’t keep your feet dry and the first opportunity they do get to be dry it cracks – it’s not just a little thing, it’s really big and any pressure on it is awful, you’re in so much trouble.

‘You don’t want to go to hospital generally – but eventually you end up passing out and wake up in hospital. You don’t put yourself there because there’s no way of getting money there.’

The Doctor asked Stephen Willott, a Nottingham GP who sees homeless patients at the Friary and is clinical lead for drugs and alcohol in the city, what help the patients he works with need. ‘It tends to be a lot of stuff relating to their being homeless – it could be mental health, or they have terrible foot care, a lot of it can be sexual health issues or to do with drugs and alcohol. Sometimes there are things we can do there and then but often it’s about making a plan. ’

Stephen Willott, a Nottingham GP

Stephen Willott, a Nottingham GP

‘If someone is alcohol dependent and living on the streets there’s no medication I can help them with or detox to arrange, so it’s working to try and get accommodation and then working out a plan as to how to get them free of dependency, if they want that. In the meantime it’s about getting them some vitamins and things like that.’

Suzey Joseph probably has more interaction with the homeless than any other professional in the area. Ms Joseph is nurse specialist for the city’s Homeless Health Team, run by NHS community healthcare provider Nottingham CityCare.

In the space of just an hour – in a cramped office behind a café in the heart of the city – she shares anecdotes that would be enough to upset even the sternest listener: tales of cancer patients who needed palliative care dying on the streets or young people who have left care being sexually and physically abused.

But almost every homeless person Ms Joseph comes into contact with is in need of serious healthcare. Living on the streets, or in and out of hostels, is simply not a healthy existence. Unfortunately, many people either do not seek help – for a multitude of complex reasons – or it isn’t obviously accessible to them, and the results are costly and tragic.

‘People just become more chronically unwell as time goes on. They get infections, organ failure and get sicker and sicker until people die on the streets. It can be so difficult. How are they going to get to an appointment?’

‘They don’t even know what day it is, let alone time. It’s pouring with rain, someone’s urinated on them, they’ve been beaten up – the last thing they are thinking about is making their Monday morning meeting. And if they don’t attend, they just get sicker and sicker until they are only attending again at crisis point.’

It is in hospitals where these patients at crisis point are usually treated. For many patients, a hospital is the most uncomfortable, unsuitable location in which to be treated at any point up to an acute episode – and hospital care is far more expensive than that which could be provided in the community.

‘We have eight people who are homeless or have housing issues currently within NUH (Nottingham University Hospitals, which runs the Queen’s Medical Centre and City Hospital) on the system,’ Kay Parker, who runs NUH’s integrated discharge team, says. ‘The longest length of stay is 242 days.’

She adds: ‘Anecdotally we are seeing more and more patients coming to the hospital and through our team and there are more complex factors as well – there is partly an increase in the numbers anyway, but we are also trying to identify people earlier. And it becomes much worse in the winter.

‘It’s not just young people, these people are in their 50s and 60s. You make the assumption that a lot of homeless people are young people, but we are also finding people in their 50s, 60s and 70s being made homeless.’

But what are the driving forces behind homelessness and the resulting demand on the health service?

Ask anyone in this city – or indeed any other in the UK – and the answers are consistent, if unsurprisingly complex:

– cuts to public health services like substance and addiction services

– lack of mental health provision

– inaccessibility of GP services

– fragmentation of the health and social care system

– and rising prominence of new psychoactive substances like mamba or spice.

Perhaps most importantly of all, too, are the obvious lack of housing or suitable beds in the community and the over-arching impacts of austerity politics.

Oblivion

When it comes to substance misuse the problem is two-pronged. Firstly, the difficulty of life on the streets means homeless people have always turned to substances, but in recent years the rise of NPSs can have even more troubling results. Secondly, support previously available to people struggling with addiction has been cut to the bone under austerity politics and since the transfer of public health to local authorities from the NHS.

Dr Willott says: ‘Everything has become a lot harder in times of austerity, without doubt. There are fewer direct access beds around, some of that is political and the fault of decisions made by councils, and there are funding cuts – the drug and alcohol service for example has had a quarter of its budget slashed in the county and that has a knock-on effect. Things have got harder. It’s still a case of trying to encourage and educate primary care to be an appropriate response to people with complex needs.’

Nottingham GP Marcus Bicknell, whose surgery welcomes homeless patients and allows them to register with the practice address, cites £7.5m of recent public health cuts in the area as having a devastating impact. Describing the patients he sees, Dr Bicknell says: ‘There are some incredibly extreme behaviours. In recent times injecting a combination of crack and heroin called a snowball or screwball into the groin is becoming a normal behaviour on the streets, which is frightening.

‘And I have a patient who chopped his earlobes off on mamba when he was psychotic. You see these most bizarre psychotic behaviours unique to these drugs, and our knowledge and understanding is still evolving and emerging.’

‘Public health services are so easy to cut – you don’t see such easy decisions being made about cuts to transport or library services.’

‘Addiction services have been hit hard, and the impact of that is serious. All the cuts seem to be in health and social care – that just can’t be right. It has a massive impact upon addiction services and eventually homelessness,’ Dr Bicknell says.

Sam Crawford, the chief executive of the Friary drop-in centre, poignantly sums up the horror of the rise of NPS. ‘We have been asking people why they use NPS because, generally speaking, people don’t have a good experience, they don’t have a good trip on it.

‘The answer really is that it’s cheap and accessible, but most importantly, that it completely removes people from reality for two hours – they don’t care if they have a good experience, it’s not about hedonism or enjoyment. It’s about totally removing themselves from society. It’s a thoroughly damning indictment of our society.

‘These people know they will have a period where they are incredibly vulnerable, they have short-term paralysis and at night in particular anything can happen: their possessions will be nicked and they are completely defenceless, but they don’t care because reality is so horrible.’

Falling through the cracks

Access to services that mitigate these issues is a real problem. As BMA public health committee chair Peter English says: ‘Homelessness involves a whole constellation of problems: poverty, debt, lack of support services in substance addiction and a whole raft of health issues.

‘Cuts to public health services play a part: we see the reports coming through about how the budgets for public health have been spent on other things – the difficulty often is that in local authorities, public health budgets are supposed to be ringfenced but money can often be spent on things like transport or roads because it might help air quality, and core services like addiction services lose out.

‘We need compassionate arrangements for people rather than punitive attitudes from Government, who think people should just take responsibility and then ignore these areas. The politics of this is important.’

The health and social care system, particularly the structures created by the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, is often the problem when it comes to the experiences of homeless patients – and resulting costs for the NHS and society. A fragmented system – where social care and individual health providers fight for their contracts and protect their own pots of cash – is not conducive to collaboration or finding the best outcomes for vulnerable, or difficult, patients.

Not only that but the NHS is notoriously poor at sharing data and recording patients, and homeless people are liable to fall through the cracks between accessing one part of the service and then needing another.

These are not patients who are always welcome, or comfortable, in reception areas; they may have complex needs that present as being difficult.

And as Ms Josephs says: ‘Even in the most caring folk, care can soon turn to contempt.’

The result of all these problems is that homeless people wait on the streets until their need for care is so acute that it can often result in needing very serious care, or that no treatment can be provided. Even if they are able to access the system successfully it is likely they will be either stuck in the wrong place – while arguments over who should foot the bill are had – or they are discharged and forgotten about until the whole process starts again.

Ms Joseph says: ‘It’s causing havoc at the hospital because they are under pressure and they need to get people in who need acute care, beds and therapy, but they can’t always move people on. There are people in there who should be able to go out much more quickly but sometimes there’s no social care available and those discussions are ongoing.

‘People get discharged all over the place: to the winter night shelter in July, to housing aid, to a GP surgery. It’s a really good thing for someone to give them a correspondence address and allow them to register but hospitals need to be able to record them better. So many people just fall through the cracks.’

Cut to the bone

A study into the mental health needs of Nottingham’s homeless population, conducted earlier this year by Sheffield University, found similar conclusions. It found that a very high proportion of homeless people in Nottingham had multiple, complex needs and that, while political will and empathy seemed to be present in the city, those needs were not being met.

Austerity, and the resulting impacts of the best part of a decade of cuts, have a major part to play – as is the case in so many parts of society and so many of the changes seen in the country over recent years. Since 2010, the year David Cameron was elected prime minister, the number of people sleeping rough in England each year – not even including those vulnerably, often very vulnerably, housed – has risen from 1,768 to 4,751 in 2017, according to estimates.

597 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2017

And figures published by the Office for National Statistics just last month (December) estimate that 597 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2017 – an increase of 24 per cent over five years.

Days spent on the streets, in the homeless shelters and with the experts in Nottingham make it abundantly clear how these numbers have risen. Safety nets no longer exist. It only takes one small piece of bad luck, or one mistake, for people to find themselves among the statistics. No wonder they rise in such exponential fashion. And when the numbers rise, the strain on the health service and society’s purse grows rapidly.

Mr Crawford says: ‘I think the austerity measures that hit local authorities have definitely brought about a much more fragmented approach to statutory services, which is problematic when you talk about people with multiple and complex needs – everyone tries to address these issues in isolation without recognition for the fact that they interrelate.

‘It’s budget first and people second.’

‘I can think of at least two people immediately who have longstanding mental health diagnoses – who are really chaotic individuals – who have magically had their diagnoses removed from them. It feels like mental health services are under pressure to get people off their books and austerity breeds that it’s budget first and people second.’

The personal stories, the number of those affected, and the costs are equally striking. But perhaps most striking of all is the fact that a serious commitment to addressing homelessness would almost certainly save money.

According to Crisis, if 40,000 people were prevented from becoming homeless for one year in England it would ‘save the public purse £370m’. A 2015 study called At What Cost found that the cost of a rough sleeper to society for 12 months was more than £20,000 – whereas a successful intervention would cost, on average, just £1,426. The clarity of the equation is as striking as society’s unwillingness to act upon it.

The checklist for solving this problem is as ubiquitous as the causes were when The Doctor asked:

The shopping list might sound expensive – but doing nothing would be much more costly. Dr English adds: ‘If this was some disease causing all these problems it would be a much higher priority, but because victims can be blamed and stigmatised, it is easy for Government to ignore.

‘The growing numbers of rough sleepers and vulnerably housed people in our society is a continuing tragedy. To stand by silently as our NHS faces increasing strain and our society becomes increasingly unequal would be unacceptable.’

If anyone needed any further convincing of why action must be taken, just think of Samantha Moss – and all those like her – on the brink of having to return to the streets of a society rich enough to help, but which chooses to ignore. As this story is published, Samantha and Clayton are deciding where they will sleep when they are evicted from their house: on city centre streets, in a tent on the embankment or back under the arches of Trent Bridge.

‘It’s just terrible,’ says Samantha. ‘Why can’t they do more for homeless people?’