The first medical student Philip Smith met on his arrival at university came from Eton.

With annual fees of more than £33,000 a year, and a list of alumni that includes 19 British prime ministers, the Berkshire public school is practically a byword for wealth and entitlement.

20 per cent of secondary schools in the UK provide 80 per cent of all applicants to medicine

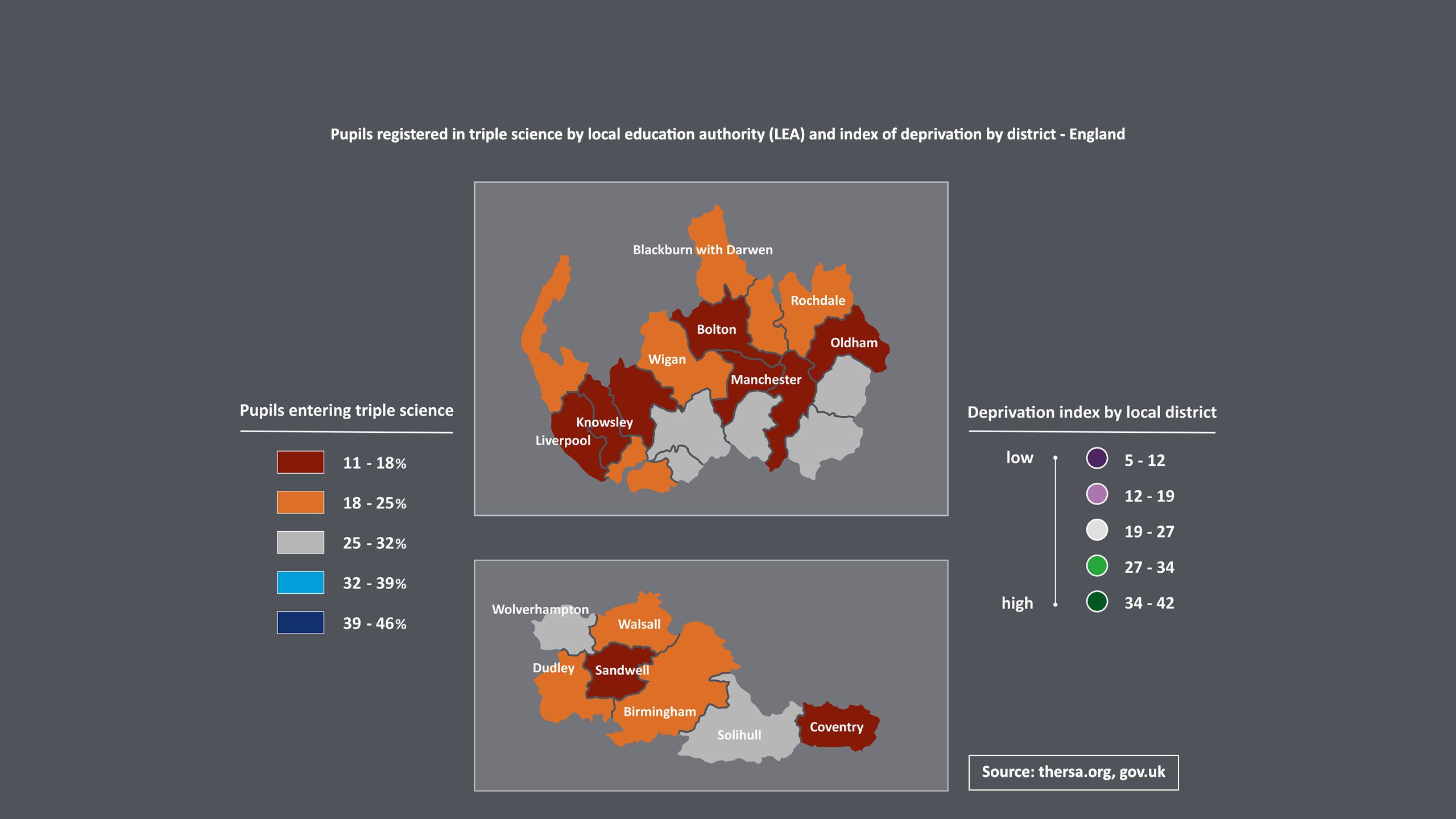

Philip’s under-resourced comprehensive in Rochdale, near Manchester, lay at the other end of the educational and social spectrum. Recently ranked among the worst places in the country for jobs and skills - the city has one of the highest numbers of people with no formal qualifications.

‘At times it was a battle to keep focus,’ Philip says. ‘In classes you were next to people who did not want to learn and who came from crazy situations. If they were seen to work hard, they were laughed at.

Philip Smith, kneeling bottom left, at secondary school in Rochdale

‘From my form class, two of the boys are now in prison,’ he adds.

Today, Dr Smith is a successful gastroenterologist at a well-respected London hospital. He is finishing a PhD, has letters after his name, and a string of publications and prizes jostling for space on his CV.

But Philip’s story is the exception – as much now as it was in the 1990s when he was at school. Pupils from backgrounds such as his are extremely unlikely to even dream of going to medical school – and any that do make it will find themselves, like Philip, surrounded by students from elite educational establishments.

The statistics are glaring: 20 per cent of secondary schools in the UK provide 80 per cent of all applicants to medicine.

Additionally, the 7 per cent of the UK population educated at independent fee-paying schools, make up 22 per cent of medicine and dentistry undergraduates and 51 per cent of the most influential doctors in the profession.

Between 2009 and 2011 half of all schools in the UK did not provide a single applicant to medicine

Even more telling is the fact that between 2009 and 2011, half of all schools in the UK did not produce a single applicant to medicine – a fact that BMA medical students committee co-chair Charlie Bell describes as ‘staggering’.

Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that the medical profession is lagging behind other fields in terms of social diversity.

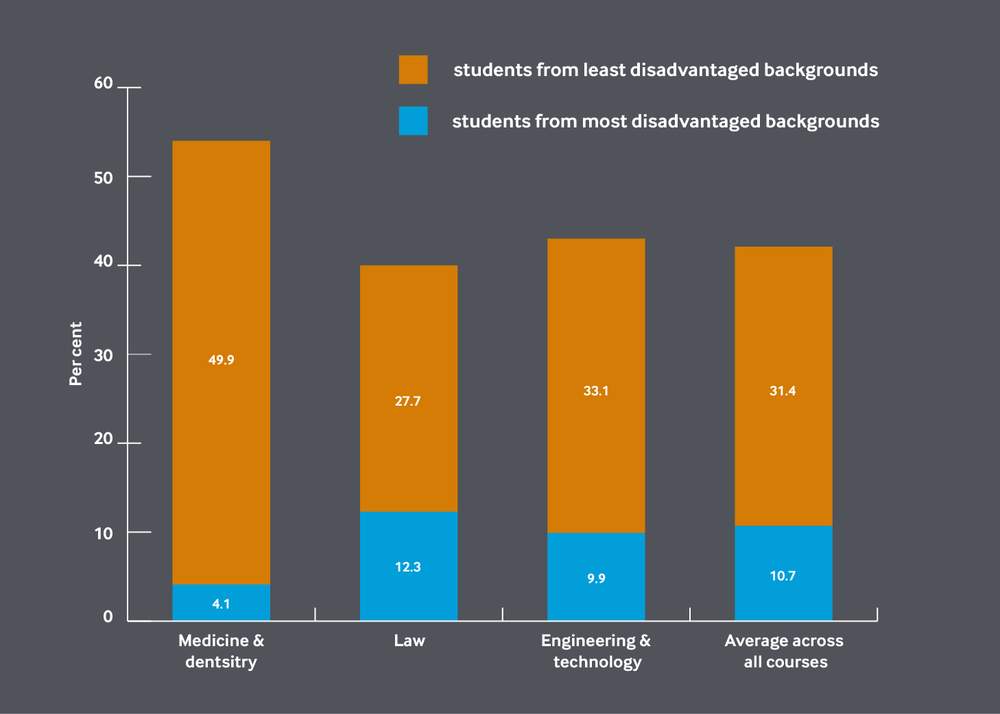

Of the 11,125 students who entered medicine and dentistry in 2011, just 4.1 per cent were from the most disadvantaged backgrounds.

This compares to law at 12 per cent, engineering at 10 per cent with the average across all higher education courses at almost 11 per cent.

Strikingly, at the other end of the spectrum, those from the least disadvantaged backgrounds made up half of students entering medicine, again compared to law at 27 per cent, engineering at 33 per cent and the average across higher education at 31 per cent.

Medicine lags behind other fields when it comes to attracting students from a variety of backgrounds (HEFCE 2014, table 43)

Three years ago, the UK medical sector was criticised for not moving quickly enough to address the issue of social diversity in an independent report titled Fair Access to Professional Careers, commissioned by the Government.

‘Since the 1970s, the UK medical student body has become increasingly diverse when it comes to gender, ethnicity and age,’ it said. ‘That progress, however, has not been mirrored by a similar change in its socio-economic background.’

‘The profession should be open to the most able, not those most able to pay’

It is clear that urgent action needs to be taken – and not simply to ensure fairness. According to the Sutton Trust think-tank, not addressing low social mobility is ‘to condemn our talented children – and our economy – to the bottom of the class in education’s new world order’.

The profession, says the BMA’s Mr Bell, ‘should be open to the most able, not those most able to pay’.

But why are students from disadvantaged backgrounds still being held back, and what can teachers, medical schools, policy makers, and above all doctors, do about it?

For centuries, medicine was dominated by middle-class white men, and women’s endeavour achieve gender equality within the profession has been long and arduous.

As retired consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology Wendy Savage details in her foreword to Catriona Blake’s book The Charge of the Parasols (1990), the establishment used a variety of tactics to keep Victorian women out.

By 2013 more than half of all medical students were female

‘They changed the university rules, resorted to legal action, manipulated the male students and attempted to intimidate the small band of women, even though there was a strong body of support for their efforts to qualify as doctors,’ she writes.

But change did come, and although many may argue that there are still too few women at the top of the profession, by 2013 more than half of all medical students were female.

In contrast, the struggle for social mobility within the profession is still in its infancy, although the chief obstacle is not outright opposition so much as inertia.

Social Mobility Foundation chief executive David Johnston says that while progress has been made on gender and increasing BME (black and minority ethnic) applicants within medicine, the balance has tipped only slightly – towards privately educated non-white males.

‘That is diversity of a form … but when that person gets to the interview room they have all the same cultural understandings [as a privileged, white male].

‘The balance has tipped only slightly – towards privately educated non-white males’

‘If you are a black Etonian, you will likely feel the same level of comfort when you come for your [medical school] interview as another privately educated person, but the white working-class boy from Barking and Dagenham or the council estate in Leicester might not.’

Data for 2013/14 shows that nearly two-thirds of medical students in the UK describe themselves as white, just under a quarter identify as Asian and a mere 2.86 per cent as black.

Professor of primary care health sciences at the University of Oxford Trisha Greenhalgh believes however, that ‘it is class, not ethnicity, that is the under-measured variable’ in attempts to widen access within the medical profession.

Professor Greenhalgh, who hails from a working-class background herself, is the co-author of a research study described as ‘the largest and most systematic sample ever recruited of 'socio-economically deprived' aspirants to medicine’.

Professor of primary care health sciences Trisha Greenhalgh

Most of the students in her study were from a first- or second-generation immigrant family background, which threw up some interesting results.

Based on the data, the researchers predicted that the ensuing years would see a rise in medical school applicants from socio-economically deprived backgrounds, but that only a few would be classified as traditionally working class.

Professor Greenhalgh says: ‘Immigrants and children of immigrants may be “working class” here, but they certainly weren’t in their country of origin – this is the ambitious migrant effect, people know that the route to a better life is qualifications.

‘It is class, not ethnicity, that is the under-measured variable in attempts to widen access’

‘I remember a Bangladeshi guy who worked for me invited me round to his house and, when I walked in, all four of his adult children were lined up in the order of their academic qualifications. He said: “This is my daughter, she is BSc” and he didn’t even say her name.’

The real issue that needs to be addressed, Professor Greenhalgh says, is the resistance shown towards education by working-class children, which fosters a disruptive counter-culture within schools. ‘So, for example, in science lessons, they would mess about and try and burn the bench with the Bunsen burner.

‘Actually, these [children] are just as bright but they resist being groomed for the next stage. One group of kids thought [about] university … you would be locked in the room and lectured on very boring topics for hours. They didn’t know about university sport or that there was any kind of social life …’

‘The middle-class child expects to become the thing they aspire to, while the disadvantaged child does not’

Of course, this is not just an issue of resistance towards education, but also of the culture within schools themselves.

The Social Mobility Foundation's Mr Johnston says: ‘What research shows is that aspiration between the average middle-class child and the average disadvantaged child tends to be pretty similar.

‘In reasonably similar proportions they want to be doctors, or architects, or what have you. But the middle-class child expects to become the thing they aspire to, while the disadvantaged child does not – that’s where the gulf lies.

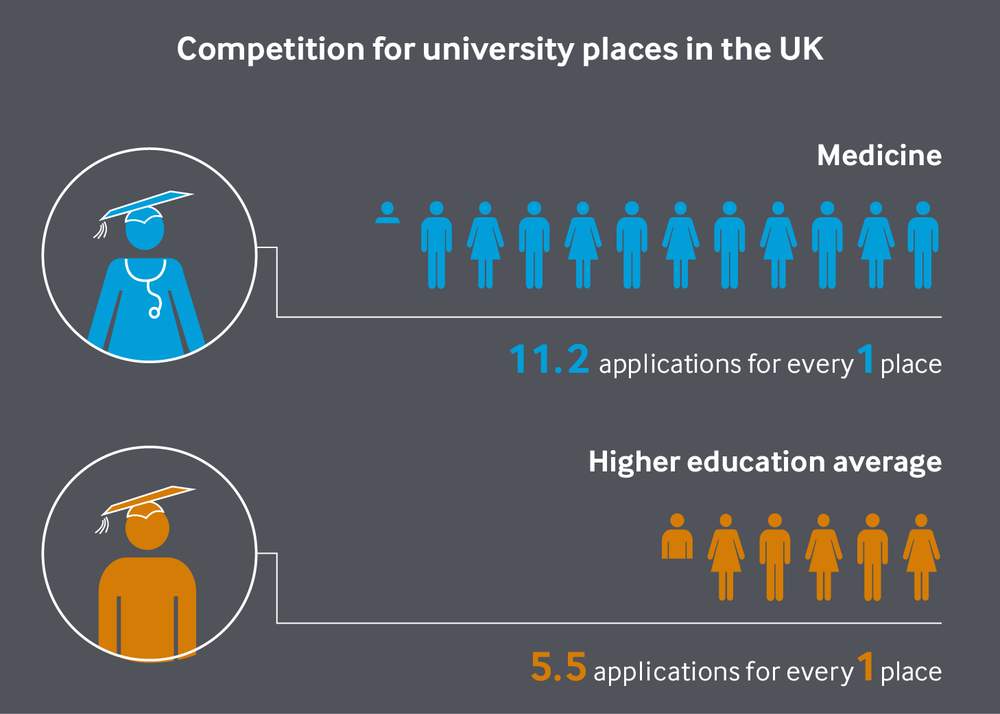

Competition for entering medicine is more than double the higher education sector average

‘They want to, but they don’t actually think they’ll get there – and there would be a fair case to say … they may be right.’

Competition for medical school places is fierce. For every place, there are 11.2 applications, compared with the higher education sector average of 5.5, according to the most recent data.

It is fair to say that such a situation favours pupils at schools with the experience to handle applications and aid their preparations for entry.

And with over 50 per cent of schools in England having not had a pupil apply to medicine in recent years, many simply lack the experience, resources and support that students require to be successful.

Dr Smith’s school was one that lacked these essentials when it came to advising a pupil about a career in medicine.

Phillip (sic) Smith featured on the front page of the Rochdale Observer

‘My school never had anybody interested in doing medicine – it was all very much a voyage of discovery for me and my mum and dad.’

In Dr Smith’s case, it was experiencing his own health problems that led him to imagine a career in medicine. From the age of 10, he spent four long years awaiting a diagnosis for his condition, Crohn’s disease. ‘I was very sick at school and in and out of hospital,’ he says. ‘I had lots of operations.’

‘My interest in medicine came from watching doctors on the ward and seeing how they behaved with others.’ This life-changing experience not only sparked an interest, but gave him the necessary motivation to pursue it.

‘It was all very much a voyage of discovery for me and my mum and dad’

Sheffield-based foundation doctor Alex Ward is another who had to look beyond school for support and inspiration. ‘I think one thing that would have had such a massive impact on me in my secondary school would have been a careers advisor saying, “Yeah, you can do that,”’ she says.

‘On a number of occasions during my GCSEs and A-levels I was told that I would never get into medicine so “give up now” by teachers.

Alex Ward, with her parents and partner, graduating from medicine

‘My school didn’t have a dedicated careers counsellor [or] dedicated time to talk about careers – the focus was very much to get out and start working.

‘I was told that I would never get into medicine so “give up now” by teachers’

‘It was only through the support of my parents [a farmer and a council worker] that I actually managed to get into medicine. They were the ones … who told me I could do it. They were the ones who actually went into school and told the teachers off for telling me such unfair things.’

Yet even with the right emotional and practical support from parents and teachers, the barriers can often appear insurmountable.

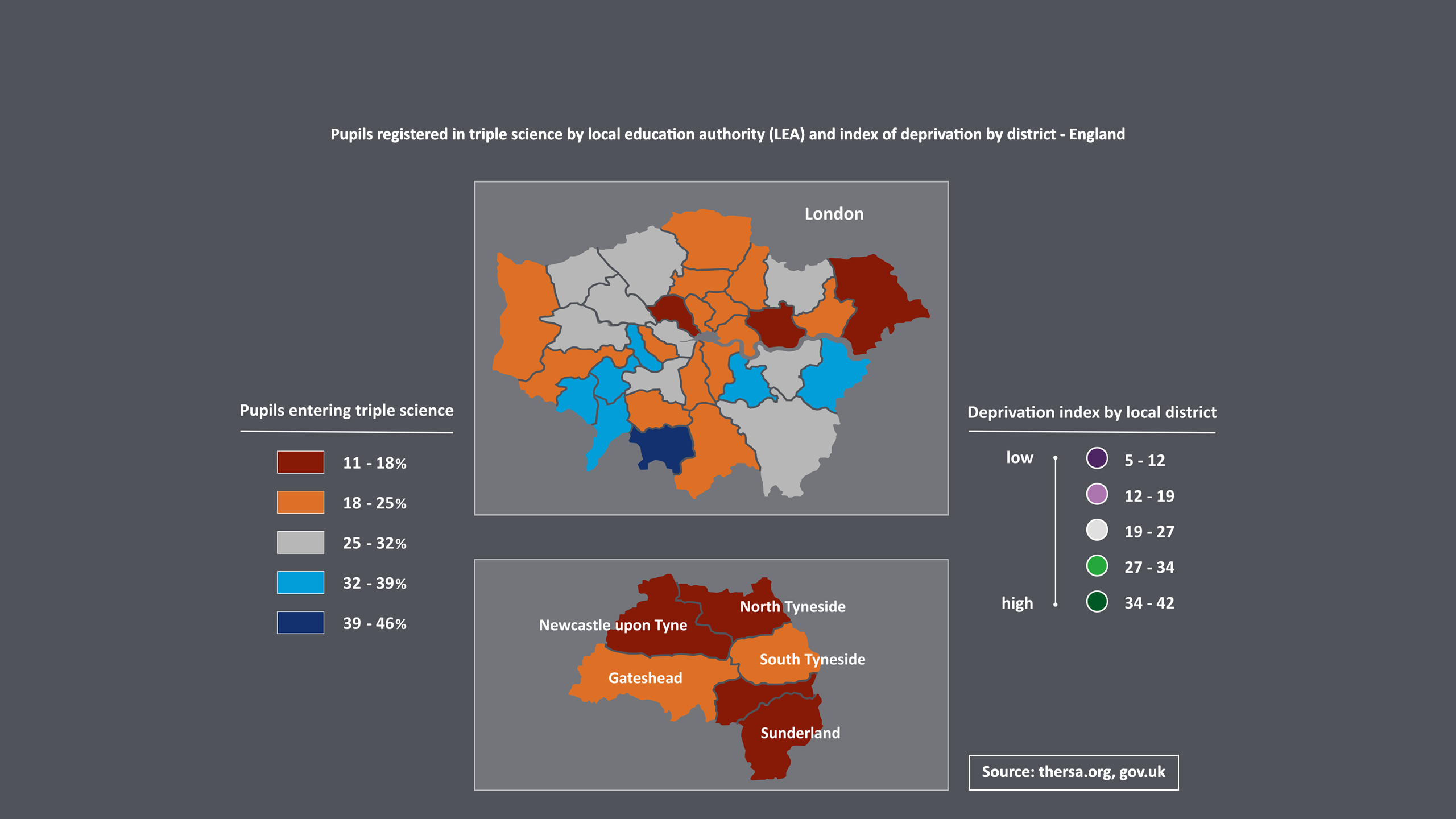

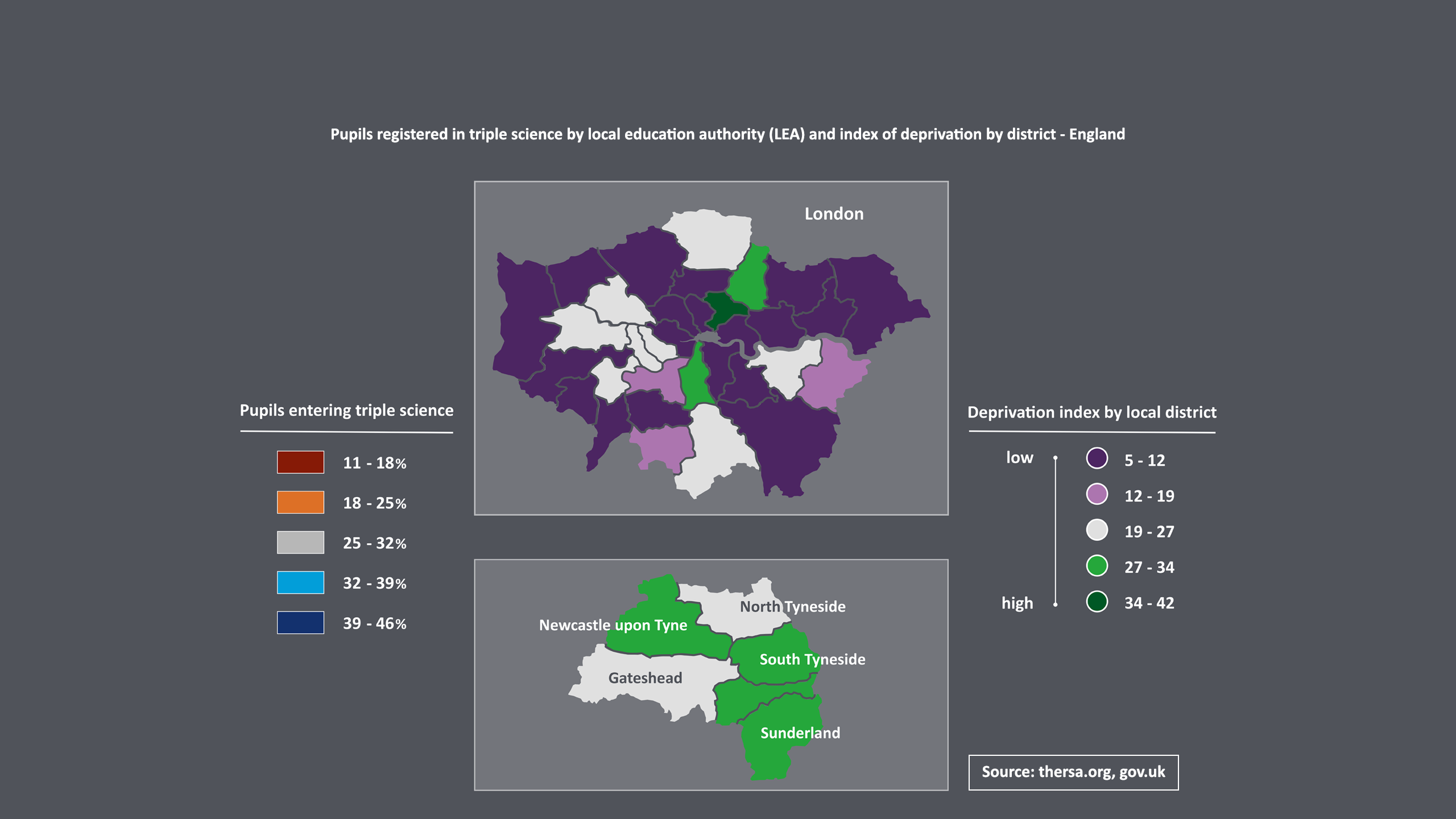

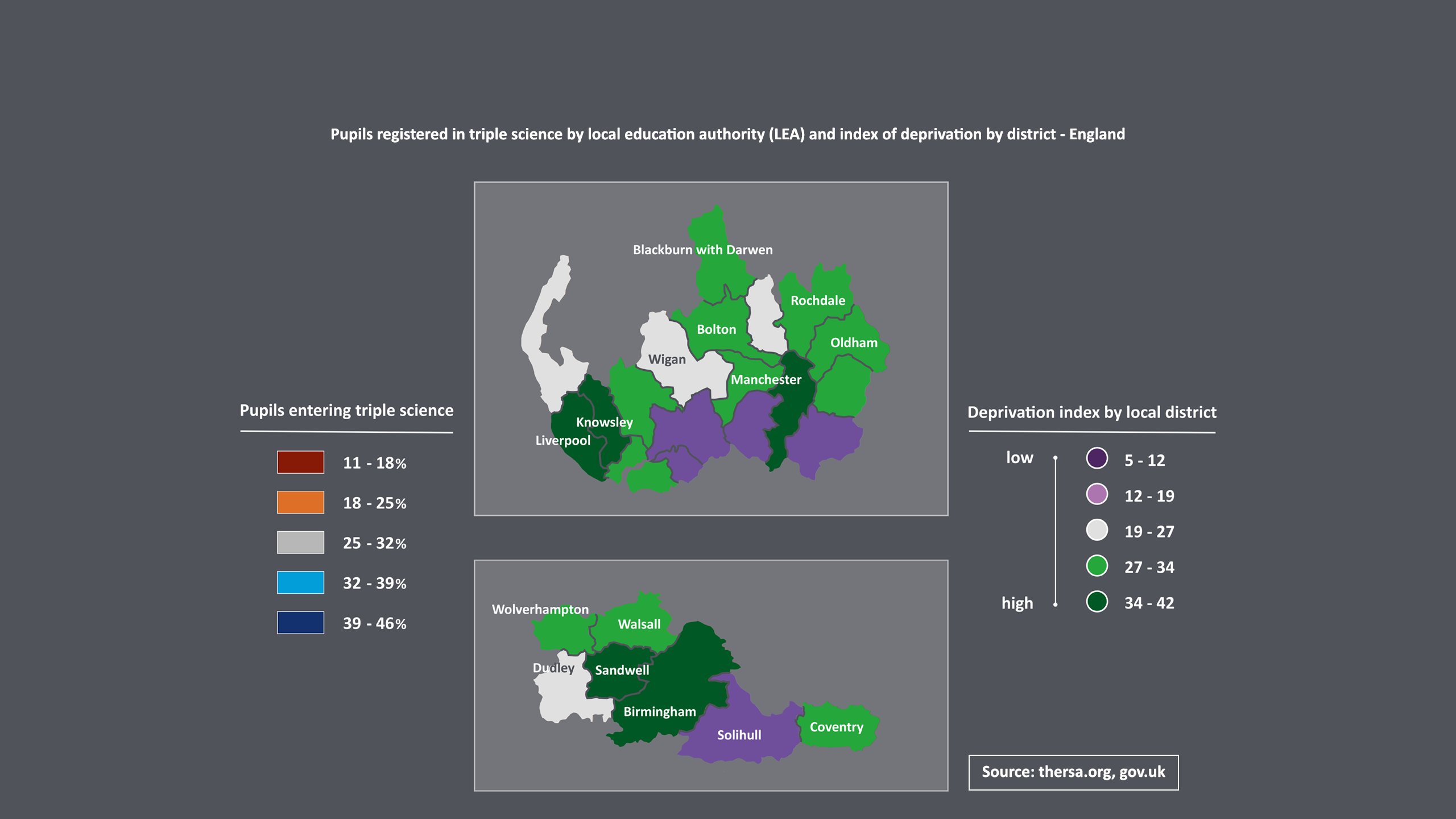

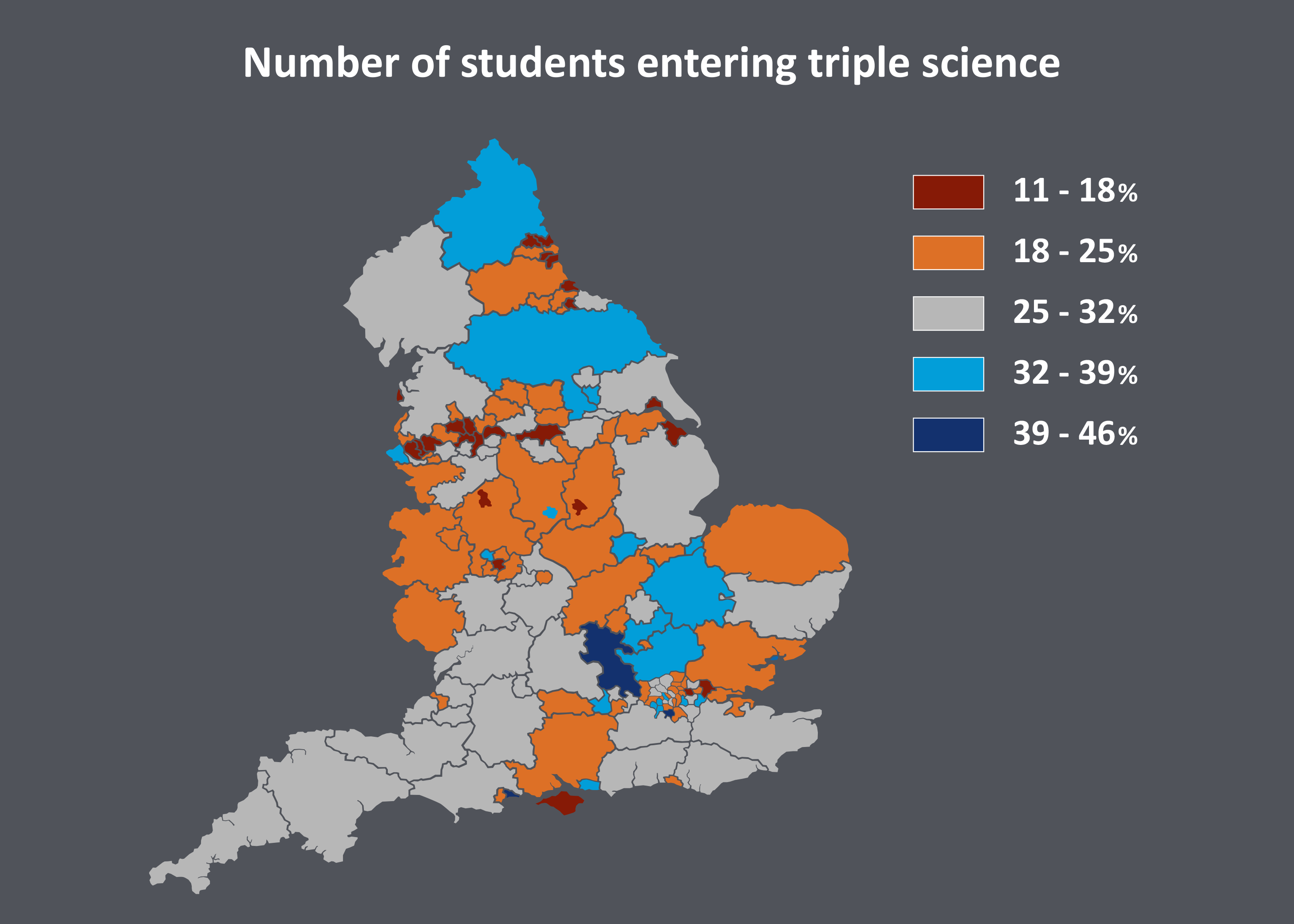

Young people who live in deprived neighbourhoods are often denied access to ‘tough’ subjects such as triple science – favoured by most medical schools – according to recent data from the OPSN (Open Public Services Network).

‘The curriculum taught to children in poorer parts of Britain is significantly different from that taught in wealthier areas’

‘Children’s educational opportunities are defined by where they live,’ says OPSN chair Roger Taylor. ‘In some parts of Britain, opportunities are restricted because all schools within a neighbourhood have decided not to offer more challenging subjects.

‘We can see that the curriculum taught to children in poorer parts of Britain is significantly different from that taught in wealthier areas.’

The OPSN data shows that in north-east Lincolnshire, 50 per cent of the schools did not offer triple science GCSE. Similarly, more than one-third of schools in Slough, Kingston-Upon-Hull and Newcastle did not enter any pupils for triple science. In contrast, in Sussex and Cumbria, every school offers triple science.

Source: rsa.org.uk

‘Our worry is [this] reflects decisions made by schools … based on calculations as to how schools can appear better on league tables,’ adds Mr Taylor.

Parents, too, may offer emotional support but often lack the necessary experience to help their children in their aspirations.

‘They struggle due to a lack of social or cultural capital connections to be able to tap into opportunities’

For example, parents of more privileged children often play a major role in securing work experience – which plays a huge part in making a successful medical school application.

'Clearly what we see from young people who have no tradition of progression to medical school is a lack of awareness of how to obtain work experience', says outreach and widening participation manager for SOAMS (Sheffield Outreach and Access to Medicine Scheme) Julie Askew.

‘They struggle due to a lack of social or cultural capital connections to be able to tap into opportunities,’ she says.

‘No one should be prevented from fulfilling their potential by the circumstances of their birth’

In 2011, the Coalition Government published its social mobility strategy, the Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers report.

'No one should be prevented from fulfilling their potential by the circumstances of their birth,’ it declared. ‘What ought to count is how hard you work and the skills and talents you possess, not the school you went to or the jobs your parents did.’

However, it is clear that, in this respect, medicine still has a long way to go.

Philip Smith, aged 21, graduating from his BMedSci (Hons) at Nottingham University

Nor do the challenges for students from disadvantaged backgrounds end with their school days. For the few who do make it to medical school, the differences between themselves and others can be stark.

‘Often, they were people with lots of money: mum and dad were very rich or they were both doctors,’ Dr Smith remembers.

The Old Etonian Dr Smith met on day one exemplifies this. He was part of a set who did ‘fabulous things’ during university vacations, he says. ‘He was out partying every night because he knew it was going to be fine. His group went on lovely skiing holidays and to Africa to save the world, funded by mum and dad.’

‘His world was very different [to mine] – people like him were expected to qualify as a doctor, and everyone in their families had been to medical school.’

‘I had three jobs at university, I knew I would have to work – my summer holidays were spent working as a lifeguard and summarising notes at a GP practice in Rochdale.’

‘For my A-level chemistry exams, our school had to borrow pipettes from another school’

Not everybody was from a privileged background, though. Dr Smith met his future wife in the first week of medical school. ‘We were in the same year and we were of a similar mind,’ he says. ‘We both came from very working-class backgrounds and we teamed up.

‘I don’t know whether either of us could have done it without the other – we really did support each other through it.’

Philip Smith and wife Beverley received doctor's bags from his grandparents on graduating from medical school

It wasn’t just the obvious social differences that made adjusting to medical school difficult.

‘I went in to the first laboratory I’d ever been to for a practical exam and I’d never seen anything like it – all that technology,’ Dr Smith says.

‘One of the guys sat next to me said, “Yeah, it was like this at my school.” Obviously he went to public school and was used to that, but for me it was just “wow”.

‘For my A-level chemistry exams, our school had to borrow pipettes from another school. Now I’ve done a PhD, I realise how cheap those bits of glass are, but that was the resource I had available to me compared with someone else.’

‘I had three jobs at university, I knew I would have to work’

The lack of social mobility in medicine is not just a problem for aspiring doctors – it’s to the detriment of patients as well.

University of Sheffield director of medical admissions Julian Burton says it’s important for the demographic of the medical profession to mirror the population that it treats.

‘The medical profession has been drawn from a more affluent, more educated and more middle-class part of the population, and that doesn’t necessarily translate well back to the population that is being served.

‘There is a desire to reconnect the profession back with the patient population.’

This is reflected in the experience of Sarah Bowers, a fourth year medical student at the University of Glasgow.

Sarah Bowers, right, with her father and younger sister in Glasgow

Ms Bowers is the first person in her family to go to university. ‘My dad is a taxi driver and my mum is an admin assistant – I never knew medicine was a career option,’ she says.

‘It was quite a rare thing [where I’m from], to go to university,’ she says. ‘There was a lack of ambition.

‘On placements there were students who had never been in high-rise flats before and they were scared’

‘There were lots of gangs, growing up. People drank and took drugs as it was the only thing to do … We were one of the first schools to have a police officer on campus to curb the violence.’

‘In a way I’ve found it an advantage coming from that sort of place as I found it easy to relate to patients. On placements there were students who had never been in high-rise flats before and they were scared. My parents and grandparents lived in high-rise flats, so this wasn’t an issue for me – it was just someone’s house.’

Sarah Bowers at the University of Glasgow School of Medicine

Tom Humphries, a third year student at the University of Sheffield’s medical school, has noticed a similar reaction to his background, particularly during his clinical placements.

‘My background has helped me on placement because probably patients feel they have more in common with me’

The son of a bricklayer and a council worker, Mr Humphries grew up in Rotherham and still lives with his parents, working as a waiter to pay his way through university.

Tom Humphries entered medicine through the SOAMS scheme run by the University of Sheffield

For all the challenges, he believes this has made it easier to build a rapport with patients. ‘I think when they hear a northern voice, there’s always a kind of a wink or a smile, and that’s it, they’re mine – they’re happy for me to take a history, to examine. They’re much more responsive to me as a person.

‘Having my background has helped me on placement because probably patients feel they have more in common with me.’

So what is being done to address the lack of social diversity in the medical profession – and what more needs to be done?

Last December, the Selecting for Excellence Executive Group, led by the Medical Schools Council, released its final report following an 18-month study into how students are selected for medical degrees.

The research particularly highlighted the need for outreach activity to expand across the whole of the UK

At the project’s outset, it was clear that medicine had fallen behind other subjects in terms of widening participation, as well as in understanding the barriers that hold many of the brightest students back from applying for and entering a medical degree.

The Selecting for Excellence report made 68 recommendations for medical schools, the Government and other organisations to take on board, and set 10-year targets to monitor these.

A major theme that emerged was that, in England particularly, greater consistency and a national approach to the problem was needed.

The research particularly highlighted the need for outreach activity to expand across the whole of the UK as many bright and able schoolchildren are missing out on opportunities through not living near a medical school.

Secondary school students talk to doctors at the BMA's mentoring event

The BMA medical students committee has worked closely with Selecting for Excellence and supports all of the group’s proposal, citing widening participation as one of its top five priorities in Future doctors, safeguarding our NHS report, published in June 2015.

One area where the BMA is already taking positive action is mentoring. The annual representative meeting in June demonstrated the organisation’s commitment to this issue by introducing 80 GCSE and A-level students from schools in Merseyside and Cheshire to 12 mentors, ranging from medical students to junior doctors, GPs and consultants.

The BMA has also had considerable success recruiting volunteers for the Social Mobility Foundation, which provides opportunities for young people from low-income backgrounds.

Following an appeal by the BMA, the number of volunteer mentors to the foundation shot up by 90 per cent.

Work experience is a key requirement when applying to medicine in the UK

One academic institution that has recognised the importance of outreach activities – and could provide a template for others – is the University of Sheffield.

Its programme – SOAMS (the Sheffield Outreach and Access to Medicine Scheme) – targets state school pupils whose parents have not been to university and who live in postcodes with low progression to university.

‘If young people who are entering the medical profession come from a range of different backgrounds then that will ensure the profession itself has a more diverse approach to treating its patients,’ says Sheffield's outreach and widening participation projects manager Julie Askew.

‘We also aim to work with young people who are at the extreme end of under-representation in medicine, such as young people who have been in care, or young people with registered disabilities.

‘We select young people each year to work with us on a sustained programme of activity, [which] will give them a broad experience of university life.

‘Many of our students who work with the young people come from similar backgrounds, so they are perfect role models.’

‘We also aim to work with young people who are at the extreme end of under-representation in medicine’

Clinical skills and science workshops, parental support, financial information, work placements, e-mentoring and a four-day residential summer school are just some of the opportunities young people are given as part of SOAMS.

‘They may have an assumption that they won’t quite fit in a medical school environment, but we want them to achieve a sense of belonging as early as possible so that they can flourish with us,’ says Ms Askew.

Tom Humphries, middle, on the SOAMS scheme at the University of Sheffield

Third year medical student Tom Humphries is one SOAMS success story.

Mr Humphries agrees he has had to work harder than some students, particularly in learning about university and how to apply. ‘I wasn’t able to get that sort of advice from my parents. As much as they’d drop me off anywhere or take me places to try and find out, they were unable to give me that advice.

‘Without things like the outreach scheme, I wouldn’t have been able to find out that information, so getting on the scheme and making sure I attended all the events was helpful.’

Mr Humphries believes an inside knowledge is required to apply for medicine, and that’s what he got from SOAMS.

Hundreds of young people who started the course between 2002 and 2012 have been helped by the outreach offered at Sheffield:

• 125 have gone on to study medicine at Sheffield

• 52 have progressed to other courses at Sheffield

• 23 have gone on to study medicine at other universities

• 221 have progressed to other courses elsewhere.

There is no joined up approach to the problem of work experience placements

Of course, more needs to be done – and doctors have a key role to play.

One of the key recommendations of the Selecting for Excellence report is for the NHS to expand the provision of work experience for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

While programmes such as SOAMS do provide a work experience placement, there is no joined-up approach to the problem.

Other professions have already addressed these issues – for example, a scheme exists where law firms make a public commitment to prioritise work experience opportunities for people from a lower socio-economic background.

School students taking part in sessions organised by St George's medical school

Some criteria have been drawn up for an NHS scheme similar to the legal programme. These include advertising work experience opportunities openly and prioritising applications from those eligible for free school meals, as well as providing reasonable travel expenses.

These have been added to Health Education England’s widening participation strategy.

Medicine does present certain practical and ethical problems when it comes to work experience – for example, it raises questions about patient confidentiality.

However, the rapid response to the call for volunteer Social Mobility Foundation mentors suggests there is a genuine appetite within the profession to help widen access, and the BMA is helping to boost the number of doctors opening their workplaces and providing experience to school pupils.

As well as being heavily involved in formal initiatives, the BMA has produced a practical guide for doctors taking on work experience students, and useful resources aimed at helping students, whatever their background, to enter medicine.

There is a genuine appetite within the profession to help widen access

Another issue examined by the Selecting for Excellence report is the failure of some schools to offer the qualifications that pupils need to apply for medical school – and the failure of universities to alter grade requirements accordingly.

This is an area that King’s College London has tackled with some success over the past two decades.

Its efforts began in the late 1990s, after Professor Sir Cyril Chantler, a consultant in paediatrics and then dean of Guy’s medical school, met the head teacher of a south London primary school at a Christmas party and agreed to speak about being a doctor at a morning assembly in Lee Green, south London.

When he asked the children for their thoughts on the role of doctors and nurses, a boy in the front row stood up and said: ‘Doctors find out what’s wrong with you, but it’s nurses what get you better.’

‘Later, I said, "He’s a very clever lad. Perhaps he’ll become a doctor,” says Sir Cyril, ‘and the headmistress turned to me and said, “No, he will not – there’s not a secondary school in Southwark, Lambeth or Lewisham where he could get the A-levels he needs to get into your medical school.”’

‘I thought that was terrible, I went back and spoke to Adrian [Eddleston], then head of King’s medical school, and said we’ve got to do something about this.’

And they did.

The EMDP (Extended Medical Degree Programme) was started in 2000 at King's College London.

Fifteen years on, the EMDP (Extended Medical Degree Programme), at King’s College London, is still unique in offering a six-year course that spreads out the first year of the MBBS over two years, with the express aim of widening participation.

‘EMDP was the flagship, the first of its kind,’ explains current co-director Jane Valentine. ‘It wasn’t something anyone else was doing and perhaps brought to the attention of others more of a need than people were willing to consider.’

All medical schools should be using contextualised admissions to widen participation

Anyone from a non-selective state school in Greater London can apply and, crucially, have their applications assessed on a contextual basis.

Dr Valentine says the admissions team considers whether applicants’ schools are lower or higher-performing schools, then varies the grade boundaries accordingly. ‘It’s very labour-intensive, but I think it’s worth it … We are trying to level the educational playing field.’

While the standard medical degree at King’s College London requires students to gain three A-grades at A-level and a minimum competency at GCSE-level, EMDP requirements vary, with King’s accepting three B-grades in some cases.

Extra places are allocated every year for the EMDP at King's College London

‘Those from schools that have done pretty well might be asked to get closer to that AAA band than some of the worst-performing.’

The 500 applications for 50 places come in October, the UKCAT (clinical aptitude test) information arrives in November and a team of three works full time to assess the data so students can be told in January.

‘People might think EMDP is an “easier” option … but actually the ratio of application to successes is widely similar [to a standard course],’ says Dr Valentine. ‘Of course, you are only competing with people from similar backgrounds. That is where it becomes fair.’

The university’s outreach schemes are also tackling the problems of under-representation of certain groups in medicine, with around 90 per cent of the EMDP cohort made up of students from BME (black and minority ethnic) backgrounds – but more needs to be done.

‘We are trying to level the educational playing field’

‘We are clearly not going to be able to solve the problem on our own with 50 places per year,’ says Dr Valentine. ‘Nationally, more medical schools will need to take on board those things – and they are.’

Selecting for Excellence believes all medical schools should be using contextualised admissions to widen participation, with it currently being at the discretion of each university.

Another ground-breaking outreach activity takes place at St George’s University of London. Its student ambassador scheme sees around 30 medical students visiting 11 primary schools across the borough and running ‘aspiration-raising’ sessions aimed at getting children interested in a medical career.

Students from Haslemere Primary take part in an outreach programme run by St George's medical school

In recent years, Haslemere Primary School in south London has selected some of its 9 to 11-year-old pupils to take part.

Almost three-quarters of Haslemere’s pupils come from minority ethnic backgrounds, and the school has a much higher than average proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals or with special educational needs or disabilities.

‘The children that we choose tend to be the ones who are from more deprived backgrounds or who we may feel benefit from this intervention,’ says assistant head Andriana Samouel.

St George's ambassador scheme sees medical students running ‘aspiration-raising’ sessions in primary schools

‘The children learn what to do in a first aid situation: how to put someone in the recovery position, what to look for if somebody is unconscious,’ she says, adding that learning how the body works and realising that doctors have gone through school too is inspirational for the children.

‘It kind of demystifies the whole medical process for them. They are really enthusiastic from the word go and bond very well with the student doctors.

‘They might think, “Well, I can do something [like this] myself if I work hard at school.” I don’t know how many of them have actually met anyone who is studying at uni.’

In the last session, pupils from all participating schools are given a tour of the university, they learn some basic clinical skills on a mock ward and take part in a ‘graduation ceremony’. And at the end of their first year at secondary school, they are invited to a summer school at St George’s.

Pupils on the scheme take part in a graduation ceremony after learning some basic clinical skills

St George’s graduate-entry course final year medical student Ceri Haddon has been a student ambassador. ‘You ask [the children] what they would like to do in the future and you get some who come out with university-related professions, but by the end this changes and some say they’d like to become a doctor,’ he says.

Targeting 9 to 11-year-olds might seem premature, but Selecting for Excellence found that this was precisely what universities should be doing. While its research acknowledged that ‘many’ medical schools do engage with primary schools, it also said this was often overlooked and not part of a wider outreach programme.

‘We would encourage all medical schools to ensure they have a coordinated primary school programme as part of their outreach activity,’ Selecting for Excellence states. ‘At this stage of the journey it is an introduction to medicine and what it involves.’

‘A lot of families assume the debt will belong to the family, not the students, so a lot of it is myth-busting’

St George's head of widening participation Helen White says one of the challenges is explaining how to finance a degree to families with no experience of higher education. ‘A lot of families assume the debt will belong to the family, not the students, so a lot of it is myth-busting.’

Ms White says explaining loans and tuition fee arrangements helps to reassure potential students that they would need to be earning more than £21,000 a year before they pay anything back. ‘We explain the repayment comes straight out of their wages and that students are paying a percentage of a wage, which is probably only equivalent to a mobile phone bill.’

Pro-vice chancellor at the University of Sheffield and Selecting for Excellence chair Tony Weetman, warns that all of his committee’s hard work will ‘mean nothing’ unless the recommendations are implemented.

Outreach must be expanded, access to work experience democratised and selection methods must become more sophisticated

If participation is truly to be widened, university outreach activities must be expanded, access to work experience must be democratised, student selection methods must become more sophisticated, and a joined-up approach must be adopted across secondary schools, medical schools, hospitals, the Government, GMC, royal colleges, UCAS and others.

‘Yes, there is work that medical schools can be doing to encourage people to apply,’ says University of Sheffield's director of admissions Julian Burton, ‘but there is work that non-academic doctors can also be doing to encourage people to apply and there is work that schools and families could be doing as well.’

The situation has arguably been made more difficult with the announcement in the summer budget that university maintenance grants are to be replaced by a new system of loans.

‘It is only by selecting the best applicants, in the fairest way, that the UK can continue to produce world-class doctors’

BMA council chair Mark Porter fears that burdening students from low-income backgrounds with further debt may prove a further disincentive to pursuing a career in medicine.

‘It is only by selecting the best applicants, in the fairest way, that the UK can continue to produce world-class doctors’ says Dr Porter. ‘The Government should be doing more to widen participation in medicine, not putting up further barriers.’

But there are hopeful signs the profession is prepared for the challenge that lies ahead.

BMA president and former children's commissioner Sir Al Aynsley-Green

The BMA’s recently appointed president and former children's commissioner Sir Al Aynsley-Green, himself the son of a coal miner, says ‘We must give youngsters from every background the opportunity to gain insights into life as a doctor.’

‘When we give life chances to others, we give ourselves the opportunity of building a profession that is fairer and more representative of the population it serves.’

And that is surely an aspiration we can all get behind.

We want to hear from you

Hear more from BMA President Sir Al Aynsley-Green, who asks: why did you want to become a doctor? And what are you personally going to do to promote and support widening access?

Read from medical students on widening participation into medicine and join the conversation on BMA communities.

Get practical advice

Want to do more? Read our guide for doctors on how to take on work experience students in the workplace.

If you're a student looking for work experience to support your application to medical school, don't miss our tips and advice for getting a placement.

Interested in studying medicine? Or know someone who is? Read our comprehensive guide on how to become a doctor.

Credits

Senior writer: Stephanie Jones-Berry

Sub editors: Anna Thomson, Nick Jones

Digital producer: Karen Lobban

Designer: Tim Grant

Data journalist: Cristian Giulietti

Videos: Lamb and Sea

Photographs:

Matthew Saywell

, Tony Marsh

, Sarah Turton, Ceri Haddon

, King’s College London, The University of Sheffield, St George’s University of London, Haslemere Primary School

, Philip Smith

, Alex Ward, Sarah Bowers

, Getty Images

Acknowledgements:

Medical Schools Council

, Social Mobility Foundation,

Open Public Services Network, Hugh Townsend, BMA Medical Students Committee, HPERU

A huge thanks to everyone who generously gave their time to this project, particularly our interviewees and the participating universities and their staff for their valuable contributions.

Also to every doctor and medical student who got in touch with us to share their stories, it is all very much appreciated.