Who are SAS doctors?

Staff, associate specialist and specialty doctors are invaluable members of NHS teams across the UK – but they continue to face discrimination

They are one of the most diverse branches of practice in the health service, make up 20% of the workforce, and play a pivotal role in the provision of hospital services.

And yet SAS doctors often fall victim to ‘gradism’– facing lack of recognition, higher levels of bullying and, in some cases, being denied the development opportunities and incentives given to other branches of practice.

We ask: who are SAS doctors? And what can be done about the challenges they face?

In 2006, in a document called The hidden heroes of the NHS, the BMA interviewed SAS doctors to find out more about this diverse group of medics.

Thirteen years later, we find out where they are now, how being an SAS doctor helped or hindered them – and what can be done about the challenges that still face the SAS grade.

‘I have been able to achieve so much’

In 2006, Meng Aw-Yong’s time was divided between work at a busy A&E department in North London, his role as a crowd doctor at Charlton and Queens Park Rangers Football Clubs, medical consultant at the now closed Earl’s Court Arena, and as a forensic physician at several London police stations.

Dr Aw-Yong as a trackside doctor

Dr Aw-Yong as a trackside doctor

Where is he now?

‘A lot has happened since 2006.

‘I have become president of the British Academy of Forensic Sciences, I am the former president of Clinical Forensic and Legal Medicine at the Royal Society of Medicine, and medical director at the Metropolitan Police.

‘I am a panel member of the independent advisory panel on deaths in custody, a medical panel member of the First-tier Tribunals service, contributing author to the Harris review on suicides in prison and winner of an HSJ award for introducing a process to improve patient safety in emergency departments.

‘In my experience, I have never felt stigmatised for being an SAS doctor outside of the NHS, which is why I have been able to achieve so much. The focus is what you can offer and achieve, rather than the fact you’re not a consultant.’

‘I have never felt supported by my employer, who despite my achievements, has never agreed to my autonomous working.

‘There needs to be a change to how SAS doctors are perceived, and that only comes through education. Education at medical school, through to royal colleges. It is everyone’s responsibility to inform and educate future doctors, many of whom are increasingly likely to choose the SAS path.’

‘I have grown as a leader’

In 2006 Vijaya Hebbar was a staff grade doctor at the Diana, Princess of Wales Hospital in Grimsby. She was driven by a desire to provide high-quality services for children with hearing difficulties.

Her work involved coordinating and implementing the national newborn hearing screening programme, testing the hearing of children at birth and monitoring them until they turned 16.

Dr Hebbar as a staff grade doctor in 2006

Dr Hebbar as a staff grade doctor in 2006

Where is she now?

‘In July 2016 I got my CESR (certificate of eligibility to the specialist register) and entered the specialist register. In March 2017 I was appointed as consultant paediatrician with a special interest in audiovestibular medicine.

‘In 2019 I became the clinical lead for paediatrics in Grimsby.

‘I have always been fortunate to have the support of my clinical director and clinical lead, who gave me the opportunities to lead on projects as an SAS doctor.’

‘However, though I was the lead clinician for paediatric audiology, management were reluctant to change the clinics to be under my name and left it under the community consultant.

‘SAS doctors do face barriers.

‘I think if SAS doctors are to progress, then consultants and employers must change. They need to appreciate and acknowledge SAS doctors’ experience and what they can bring to the table.’

‘Being an SAS doctor in a unit, and working with consultants who have been very supportive, has enabled me to grow and mature as a leader. It has given me the skills needed to be an effective consultant.

‘I have found that by aiming high and taking on challenges and being proactive, I have been able to seek out opportunities to develop – it has allowed me to be where I am today.

‘Equally consultants and management need to encourage SAS doctors, provide them with support and projects to enable them to grow.’

‘The SAS role has afforded me flexibility’

In 2006 Victoria Hewitt was an associate specialist working in Sunderland.

She was working towards redefining the way palliative care services were delivered to patients in the north of England through the auspices of the Northern Cancer Network, a body set up in response to the then Government’s NHS Cancer Plan.

Dr Hewitt as an associate specialist in 2006

Dr Hewitt as an associate specialist in 2006

Where is she now?

‘Since 2006 I have pursued my passion for teaching.

‘Alongside my clinical work, I am now a curriculum director for MSc oncology and palliative care e-learning at Newcastle University. I have developed a series of online courses for prescribers and healthcare professionals on opioids, addressing the global effort for reform.

‘Both roles have conflicting demands, but I feel I’m a better clinician because of my teaching and vice versa.

‘The SAS role has afforded me flexibility, and therefore I am in the fortunate position to be able to say yes to these opportunities. If I had followed the consultant route, I may not have been able to do the same.’

‘In 2019 I feel respected in my field but back in 2006 it was a completely different situation. I felt like a second-class citizen; it’s fantastic to say that things have gradually started to improve over time.

‘However, my employer remains unsupportive, pertaining to the traditional hierarchical belief that because I’m not a consultant I’m not as experienced.’

‘The SAS profession is such a diverse group, and the NHS can no longer be prescriptive in the way it treats us. We have a wealth of experience so therefore change must come from us. We are here to stay, we are happy in our skin, our roles and we just need to keep going.

‘The future is what we make it. There’s opportunities ahead; we have to be confident to make it what we want.’

‘More opportunities should be available to SAS doctors’

In 2006 Amer Jafar was a staff grade doctor who revolutionised the prevention and treatment of strokes in his local area of Gwent, South Wales. With a consultant colleague, he established the area’s first Stroke Prevention Clinic.

Dr Jafar as a staff grade doctor in 2006

Dr Jafar as a staff grade doctor in 2006

Where is he now?

‘Since 2006, I have been regraded to associate specialist and as part of this role I cover the out-of-hours service for community hospitals in south Gwent, covering about 110 patients in rehabilitation/community hospitals.

‘I also have an honorary contract as a lecturer at the Cardiff University School of Medicine where I supervise the care of the elderly teaching programme for fourth-year medical students. I am also one of the supervisors for senior clinical projects.

‘I am a member of the hyper-acute stroke team at the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, which allows me to continue building my skills in stroke medicine. In 2016 I started a project called Talk Stroke, which educates the public and trainee doctors about stroke, its causes and risk factors, and how to manage it in the community.

Dr Jafar speaking at the BMA SAS doctors conference in 2019

Dr Jafar speaking at the BMA SAS doctors conference in 2019

‘The flexibility in my role and being near the frontline medical team responsible for the acute and post-acute care of patients allows me to play a significant role in the management of patients themselves, especially stroke and transient ischemic attack patients.

‘With the job plan I negotiated, I can focus on my clinical career in addition to my educational role within the university – a flexibility unique to the SAS role – allowing me to focus on the areas of my job I enjoy most.’

‘There are additional roles I’d like to play – implementing my ideas to improve the working environment of doctors, being part of the recruitment team for SAS doctors and clinical fellows in my department, being part of workforce planning and strategic plans for the health board, but it seems these opportunities are only available to consultants.

‘Health boards in Wales should open managerial jobs to SAS doctors.

‘The main challenge for the future of SAS doctors in Wales is the medical workforce and vacant posts remaining unfilled. This will only increase the pressure on SAS doctors.

‘Recruiting doctors as clinical fellows and not as SAS doctors, for financial reasons, will not solve the issue. We need competent doctors who are well-trained to manage the duties of being SAS doctors, working independently in their field of medicine.

‘CESR and the new associate specialist roles are important developments to attract more applicants to the SAS grade. The NHS needs this grade to continue and to provide a good service. The productivity of SAS doctors in the care of the elderly in Wales, for example, is comparable to that of consultants.’

What can be done about the challenges SAS doctors face?

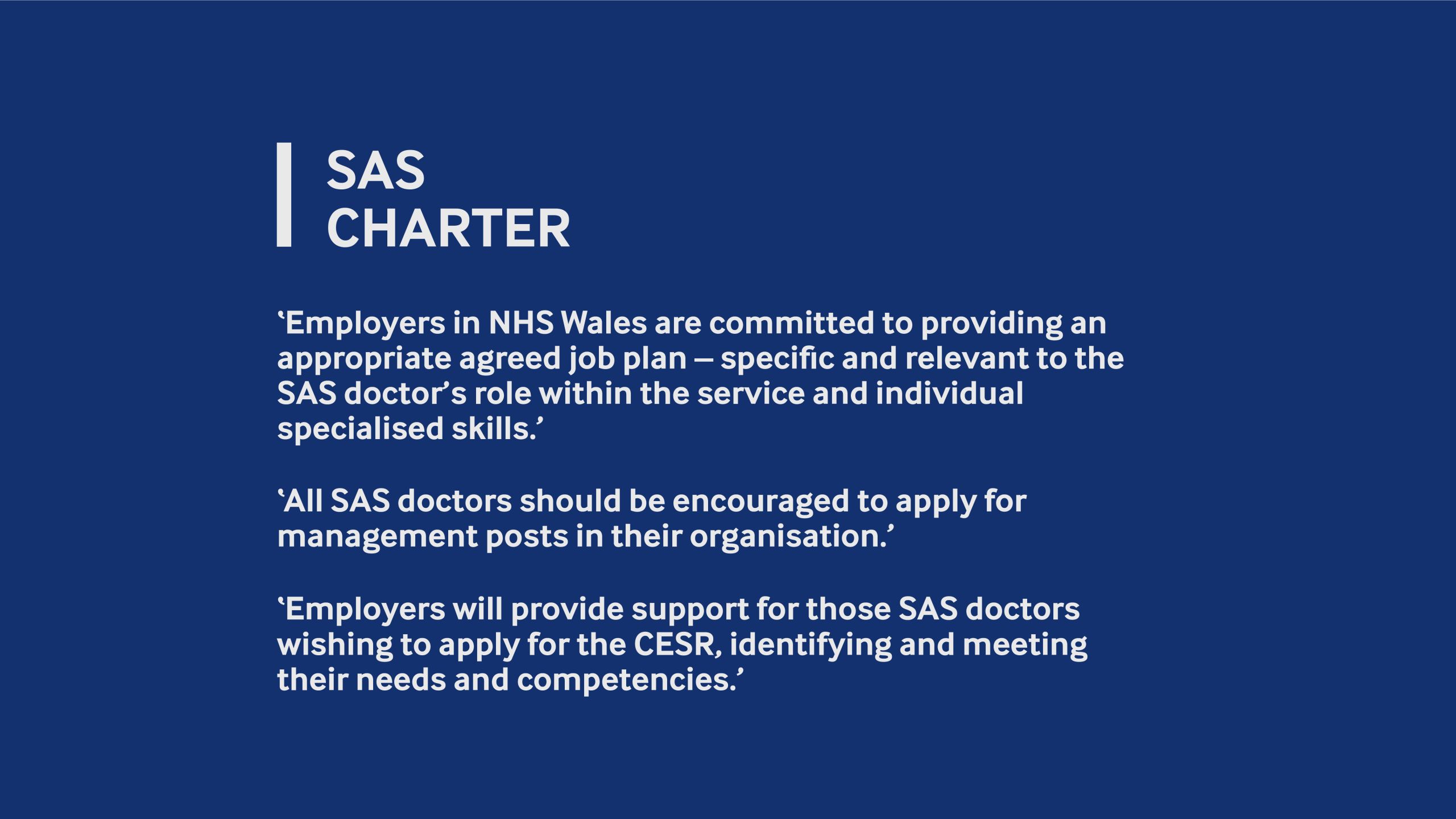

Since 2006, the BMA SAS doctors committee has been working hard to improve the working lives of SAS doctors. One of the biggest developments has been the SAS charter.

The charter takes key themes from the 2008 contract, and the main issues facing SAS doctors, and puts in place a set of guidelines by which workplaces should operate.

It is vital for holding your employers to account and providing greater development and working opportunities.

The charter themes are:

– minimum conditions of employment

– revalidation, appraisal and job planning

– helping SAS doctors to be effectively supported

– opportunities for development

– involvement in management structures.

Although the charter was published in 2014, a 2017 survey revealed that 53% of SAS doctors were not aware of it and 65% didn’t know if it had been implemented by their employer.

Here are five things employers can do to start implementing the charter:

1. Education and training

Develop a CESR training programme to incentivise new applicants to the trust / health board, and guide interested SAS doctors to make a CESR application to the GMC.

2. Job plans

Engage with consultants to encourage support for SAS doctors to develop job plans that reflect their role, taking into account workload, flexibility and professional development.

3. Rebranding the SAS role

Develop an internal campaign to raise the profile of SAS doctors’ roles in the trust so it is recognised as a senior medical role in terms of credibility and capability.

4. Resources

Work with individual SAS doctors to explore any issues around access to resources.

5. Support

Develop mechanisms for SAS doctors to raise concerns if faced with difficulties in the workplace.